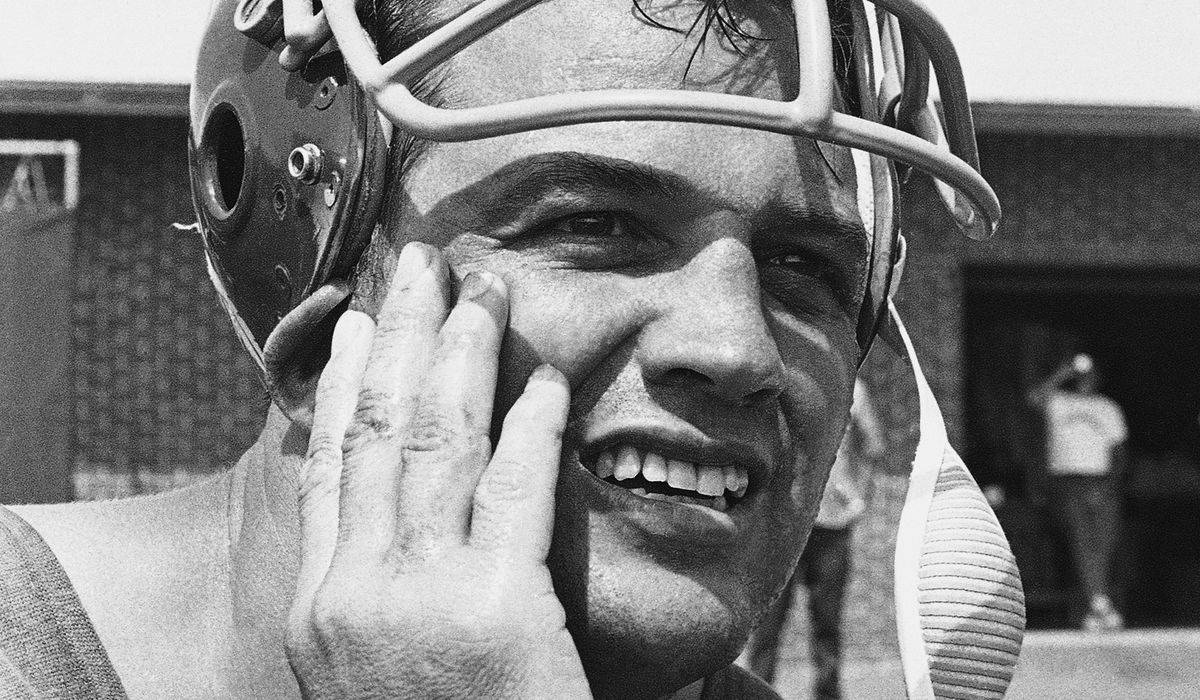

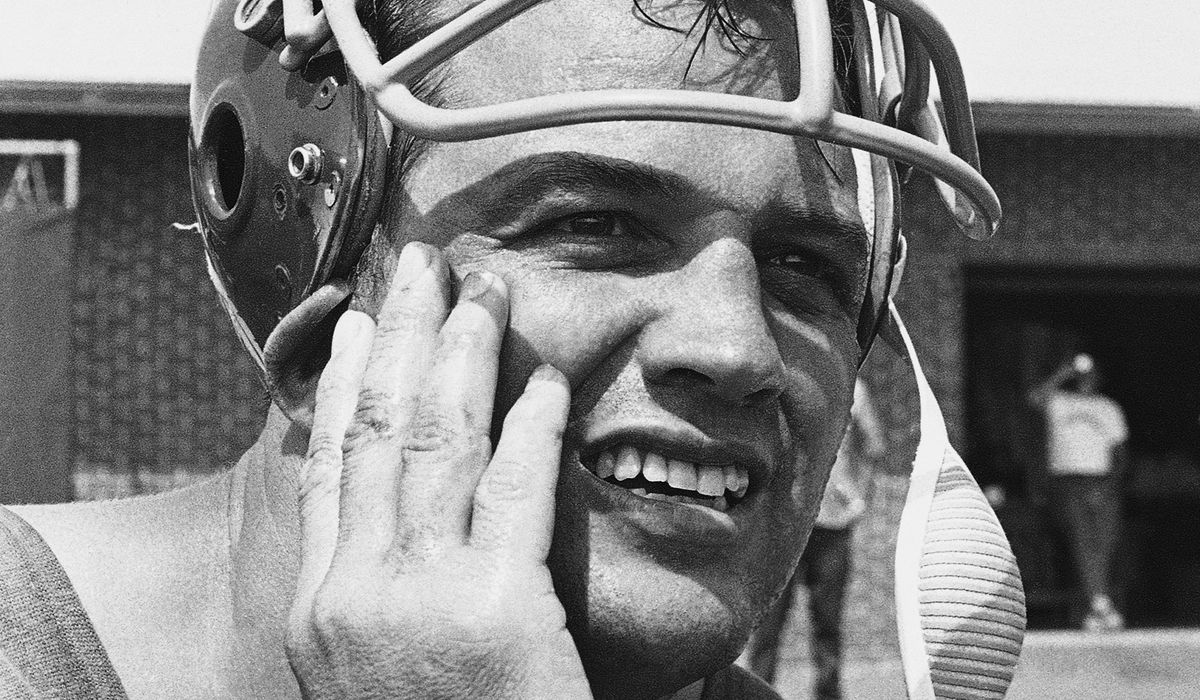

Sam Huff started small but became larger than life. He was born in 1934 in a small mining camp in Edna Gas, West Virginia. It’s a place that no longer exists.

He grew up in another small mining camp called Consolidated Coal Company Number 9. This would be the coal mine where 78 miners died in a 1968 explosion.

“We lived on an old dirt road in a small row house owned, of course, by the mine, which lacked even the smallest of luxuries, like running water,” he wrote in “Controlled Violence,” his autobiography. “Since we didn’t have a bathroom, there was a community pump outside for water and an outhouse located about 50 yards up the hill behind the house. Times were hard for everyone.”

Huff would emerge from these forgotten surroundings to become a star not just in one, but two of the most important cities in the world — New York, where he became a Hall of Fame linebacker, played in multiple title games and led the Giants to the 1956 NFL championship, and Washington, where he finished his storied playing career and began another as one of the beloved radio voices of the franchise for nearly four decades.

Both cities are mourning the passing of Huff, who died Saturday at 87.

They are remembering his legacy as one of the players that helped put the modern NFL in the front row and brought joy to fans with his colorful commentary.

“Sam was one of the greatest Giants of all time,” New York co-owner John Mara said in a statement. “He was the heart and soul of our defense in his era.”

Huff’s heart and soul were ripped out when he was traded to Washington in 1964. “I was surprised when I got traded,” he told me in an interview for my book, “Hail Victory.”

“I was 29 years old and felt like I was on top of the world,” he said. “We had just finished playing in the world championship game in January. You lose 14-10, with seven turnovers against your team. But you’re still able to hold the other team to 14 points. I was feeling pretty high. I was working for the J.P. Stevens Company in New York, doing a lot of things, like radio and television. And all of a sudden the rug is pulled out from under you. You’re traded to the Redskins, a team you competed against and beat on a regular basis. Now all of a sudden it happens. I was surprised and depressed.”

But a second life in football would emerge in Washington and a lifelong friendship. Two weeks earlier, quarterback Sonny Jurgensen had been traded to Washington. Huff, the ferocious middle linebacker, hated quarterbacks, but he would learn to love Jurgensen, as the two of them grew close as teammates and even closer as a radio broadcasting team for Washington in the glory days of the organization — when people listened.

“He came from the Eagles, a championship team, a good football team, and I came from the Giants. He knew he had to build up the offense and I knew we had to build up the defense. They developed that side of the ball a lot more than we were able to develop the other side of the ball.”

Huff never lost his passion for the game, whether it was on the field or in front of the microphone. And, like many great athletes, he embraced grudges and never forgot a slight — like this one from Pete Gent of the Dallas Cowboys.

“Sonny and I roomed together at the time,” Huff said. “We were staying at the Dallas Marriott. I was watching this Dallas Cowboys show. They had Pete Gent on, who later wrote the book called ‘North Dallas Forty.’ He has his own television show and he is giving a scouting report of the Redskins. He gets to me and says, ‘Number 70 in the middle, 11, 12 years in the league, no longer the great star that he once was. He should have retired years ago.’ I said, ‘Who is this guy?’ I nearly tore up the television. I was so mad.

“I figured, ‘How am I going to get this guy?’ He plays wide receiver. He doesn’t come across the middle. But I am going to get a shot at this guy. I didn’t sleep all night. That’s how mad I was.

“I figured the only way I could get Gent was to make a deal with Don Meredith. When we go out before the game to flip the coin, Chuck Howley, who was a teammate of mine from West Virginia, he and Meredith are the captains of the Cowboys, and me and Sonny are the Redskins captains. I said to Don, ‘Dandy, I need a favor today.’ He said, ‘What do you need, Sam?’ I said, ‘Pete Gent doesn’t think I can play this game. Bring that guy across the middle on a pass pattern. I want to hang him out to dry. I’ll show him who can play this game.’

“He said, ‘OK. I told him to keep his mouth shut.’ I said, ‘Just bring him across the middle. I’m going to kill that guy.’

“Well, we didn’t develop a signal for when he was going to come across the middle. And we’re leading 14-0 and hell, I’ve already forgotten about Pete Gent. I’m happy leading 14-0. So I was calling the defense and I told Chris Hanburger that we were going to blitz, a double blitz. ‘I’ll go up the middle and you go from the outside.’

“’We’re going to get Dandy.’ I go up the middle and nobody blocks me. They blocked Chris because they expected him to be blitzing, but I come up the middle. Dandy is standing there with the ball. I hit him in the chest, knocked him down, and he’s unconscious. This turned out to be the very play that he had Pete Gent go over the middle. This was the guy who was trying to help me get Gent, the guy I made the deal with, and I knock him out. Then Craig Morton threw two touchdowns to tie the game.”

That revenge didn’t go as planned. But another legendary one — Nov. 27, 1966 — turned out better.

“I looked at the film leading up to that game and I looked at the Giants offense and defense,” Huff said. “Normally, I just look at the offense. But it was one of the worst teams I had ever seen. It was the worst defensive team in the history of the NFL. I just knew we were going to beat them because they were just awful.”

Washington led 69-41 with about 20 seconds left in the game when Huff delivered his final blow against Allie Sherman, the Giants coach who had traded him.

“Our offense was on the field and it was fourth down. Otto Graham was our coach, but he didn’t yell for the field goal team. It was me. I said, ‘Field goal,’ and Charlie Gogolak goes in and kicks a field goal with seconds remaining on the clock to make the score 72-41.

“That was a revenge game for me,” he said. “I’ll never forget looking across the field at the guy who changed my life and traded me. I looked across the field and up to the sky and said, ‘Justice is done.’”

When Huff played, he was justice — the judge and jury. And when he called Washington football games, he was the prosecutor and defense attorney for what he saw on the field. And fans loved him for it.

You can hear Thom Loverro on The Kevin Sheehan Show podcast.