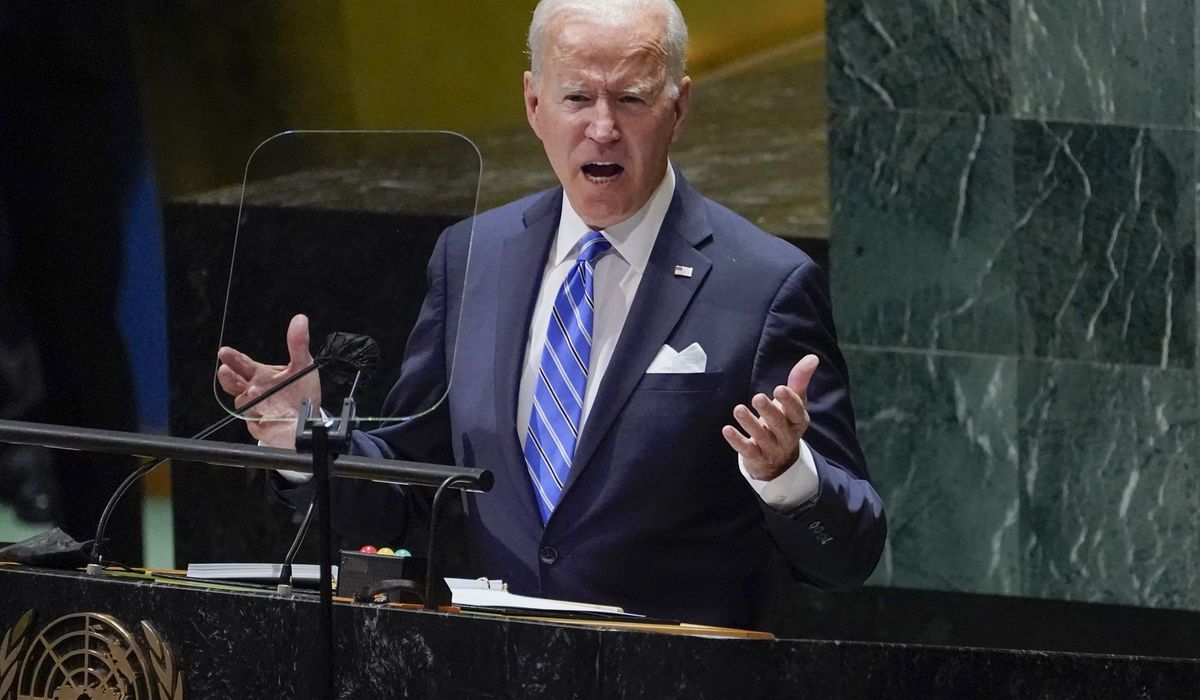

President Biden sought to reinvigorate America’s image as a world leader in a speech at the United Nations on Tuesday, brushing aside criticism from allies that he has ignored their concerns on issues including Afghanistan and COVID-19.

The speech before the annual U.N. General Assembly, Mr. Biden’s first as president, kicked off a week of diplomacy designed to recast America as a dependable ally at the forefront of efforts to combat climate change, COVID-19 and cybercrimes.

“I know this: As we look ahead, we will lead. We will lead on all of the greatest challenges of our time, from COVID to climate, peace and security, human dignity and human rights, but we will not go it alone,” he said.

Mr. Biden didn’t mention concerns from NATO allies about his go-it-alone approach to exiting Afghanistan. Several allies urged Mr. Biden to push back his self-imposed Aug. 31 withdrawal deadline but felt impotent when he refused. Others griped that the chaotic withdrawal left them scrambling to evacuate their own citizens ahead of a Taliban takeover.

Mr. Biden defended the Afghanistan withdrawal. He said it was a step toward repositioning the U.S. to head up the global battle against inequity and poverty.

“All the unmatched strength, energy, and commitment, will and resources of our nation are now fully and squarely focused on what’s ahead of us, not what was behind,” he said, noting that the U.S. is not at war for the first time in 20 years.

Republicans said Mr. Biden is failing the leadership test on the world stage. Rep. Michael T. McCaul of Texas, the top Republican on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, said the president’s speech “does not match his actions.”

“His failed leadership led to the chaotic and deadly withdrawal from Afghanistan that abandoned our partners, angered our NATO allies and emboldened our adversaries,” Mr. McCaul said in a statement. “He’s on the verge of giving [Russian President Vladimir] Putin a major victory by allowing the Nord Stream 2 pipeline to be built while turning his back on our Central and Eastern European partners.”

He said of Mr. Biden, “And his eagerness to return to the flawed [Iranian] nuclear deal is only encouraging Iran’s nuclear provocations. All the while, China is ratcheting up its aggression in the region and its malign influence around the world. Tough talk is useless if it’s followed by weak actions.”

The General Assembly’s meeting was a return to relatively normal sessions. Last year’s in-person assembly was canceled because of the pandemic.

After his remarks, Mr. Biden met in New York with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, Iraqi President Barham Salih and, later at the White House, with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Mr. Johnson praised Mr. Biden’s speech, saying it was important that the U.S. is taking charge in the global fight against climate change.

“It is fantastic to see the U.S. really stepping up and showing a lead,” Mr. Johnson said.

Also at the U.N., Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that China will no longer build coal power plants in other countries.

The announcement, during a pre-recorded speech, amounts to a policy reversal by China and appears to indicate that Beijing has yielded to months of pressure from the Biden administration on the issue.

On Friday, Mr. Morrison and the prime ministers of India and Japan — the Pacific alliance dubbed “the Quad” — will join Mr. Biden at the White House for meetings. The leaders will discuss containing China’s military expansion in the Indo-Pacific region.

The meetings are part of Mr. Biden’s push to bolster international partnerships. In his U.N. speech, Mr. Biden argued that diplomacy, not military conflict, is the solution to the world’s problems.

“Today, many of our greatest concerns cannot be solved or even addressed by the force of arms,” he said. “Bombs and bullets cannot defend against COVID-19 or its future variants.”

Despite his call for an era of “relentless diplomacy,” Mr. Biden faces skepticism, if not downright hostility, from leaders abroad. He has fractured U.S. alliances, angering partners over the bungled military withdrawal from Afghanistan and COVID-19 policies, including allegations the U.S. has hoarded vaccines.

Mr. Biden last week infuriated France, America’s oldest ally, by undercutting a $66 billion submarine deal it had inked with Australia. France blasted the move, which cost it hundreds of thousands of jobs, and recalled its ambassadors to both countries.

Ahead of their meeting together, Mr. Biden and Mr. Morrison sidestepped questions about France’s frustration over the submarine deal.

Instead, they exchanged kind words and highlighted the benefits of their trilateral security agreement, which also includes the United Kingdom.

In pre-recorded remarks at the U.N., Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi said the U.S. had no right to lecture other nations. Still smarting over sanctions imposed on his nation by President Trump, he said the U.S. “project of imposing Westernized identity [has] failed miserably.”

“Today, the world doesn’t care about ‘America First’ or ‘America is back,’” he said, taking a jab at Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump.

Mr. Biden appeared to look past the criticism and instead focused on his message of solving problems through cooperation.

Turning toward climate change and COVID-19, Mr. Biden emphasized that the U.S. will not move unilaterally or dictate the world’s direction. Rather, he said, the U.S. will work in lockstep with its partners to address crises.

“We must choose to do more than we think we can do alone so that we accomplish what we must together,” he said.

The president insisted that the U.S. isn’t looking for another cold war with China or Russia, although he didn’t mention them by name.

Mr. Biden pledged to battle terrorism by working with local partners, not through large overseas military deployments. He noted that the world has changed in the 20 years since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

He also stressed the need to combat climate change, noting that his administration pledged to spend $100 billion to help developing countries combat the climate crisis and vowed to work with Congress to double that amount.