China has launched a fresh crackdown on religious groups’ online activities in the communist nation, announcing rules that will effectively block almost all internet-based ministry that is not state-sanctioned starting in March.

Anyone who uses the internet and religion “to conduct activities that endanger national security” will face government security agencies that “will prevent and handle domestic organizations, and individuals colluding with foreign ones” in such actions, a report said.

Despite creating some of the world’s most powerful web-based brands, China‘s communist leadership has been a global pioneer in policing political and anti-government speech online, erecting what critics have dubbed the “Great Firewall of China.” The regime in Beijing is also deeply sensitive to religious figures and movements — such as the Dalai Lama, the Falun Gong movement and the Catholic Church — that it considers beyond its control and regulation.

The regulations, first announced Monday, were widely seen as an extension of those twin repression campaigns.

Chinese officials are “very wary of any so-called ‘foreign influence,’” said Gina Goh, Southeast Asia regional manager for International Christian Concern, a human rights group in Silver Spring, Maryland. “They feared that Western influence, including Christianity, [might be] bringing universal human rights principles [and] the concept of democracy. So they are very afraid of this type of exchange of information. It really is a collective effort to kind of wall out all this foreign influence.”

Ms. Goh said the restriction on foreign-owned religious websites is another way China can “cut the connection between China and overseas organizations or religious groups.”

Nury Turkel, vice chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, said these “new measures on religious activities online are another set of problematic restrictions that aim to tightly control religious practice in China.”

Mr. Turkel, a Uyghur Muslim who found refuge in the United States, said the commission was calling on China “to repeal these problematic restrictions and allow all religious communities in China to freely practice their religion.”

Ironically, Beijing singled out Mr. Turkel and three fellow USCIRF commissioners this week for sanctions in retaliation for Biden administration sanctions on Chinese officials dealing with Uyghur policy.

According to the state-controlled Global Times newspaper, “Overseas organizations and individuals are not allowed to operate online religious information services within the Chinese territory,” and “any Chinese organization or individual that operates online religious information services should submit [an] application to provincial religious affairs departments.”

The rules were joint products of China‘s National Religious Affairs Administration, the Cyberspace Administration of China, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the Ministry of Public Security, and the Ministry of State Security, the report said.

The Global Times reported that the “Measures for the Administration of Internet Religious Information Services” are intended “to standardize online religious information services and guarantee citizens’ freedom of religious belief.” The article did not explain how regulating content and banning overseas content producers promote such freedoms.

“Online preaching should be organized and carried out by religious groups, temples, and churches and religious colleges that have obtained the Internet Religious Information Service Permit,” the report said.

Those granted permission are allowed to “preach religious doctrines online that are conducive to social harmony and civilization, and guide religious people to be patriotic to the country and abide by the law,” the report continued.

“Religious ceremonies,” which were undefined, cannot be recorded or broadcast online, the rules state. Also, “no organization or individual can fund-raise in the name of religion on the internet.”

Only websites, applications and online forums that are “approved by law” may be used to transmit religious information, officials said, and “participants shall register using their real names.”

Although “screen names” are popular among internet users worldwide, they can be used to mask the identity of an individual commenting or participating in an online meeting. The “real name” requirement of the new Chinese measures would give the nation’s security apparatus a way to track people deemed security threats.

China‘s “Great Firewall” blocks access to many overseas websites, making it difficult for religious people to reach online destinations outside the nation if the government wishes to block these, Ms. Goh said. Using a virtual private network, or VPN, might help get around some restrictions, but such technology may be unfamiliar to older users in China, she added.

“If you want to set a website outside of China and cater to Chinese Christians, that’s, of course, possible, but because they have the ‘Great Firewall,’ if the Chinese Christians really want to access the information, they will need to install [a] VPN,” Ms. Goh said.

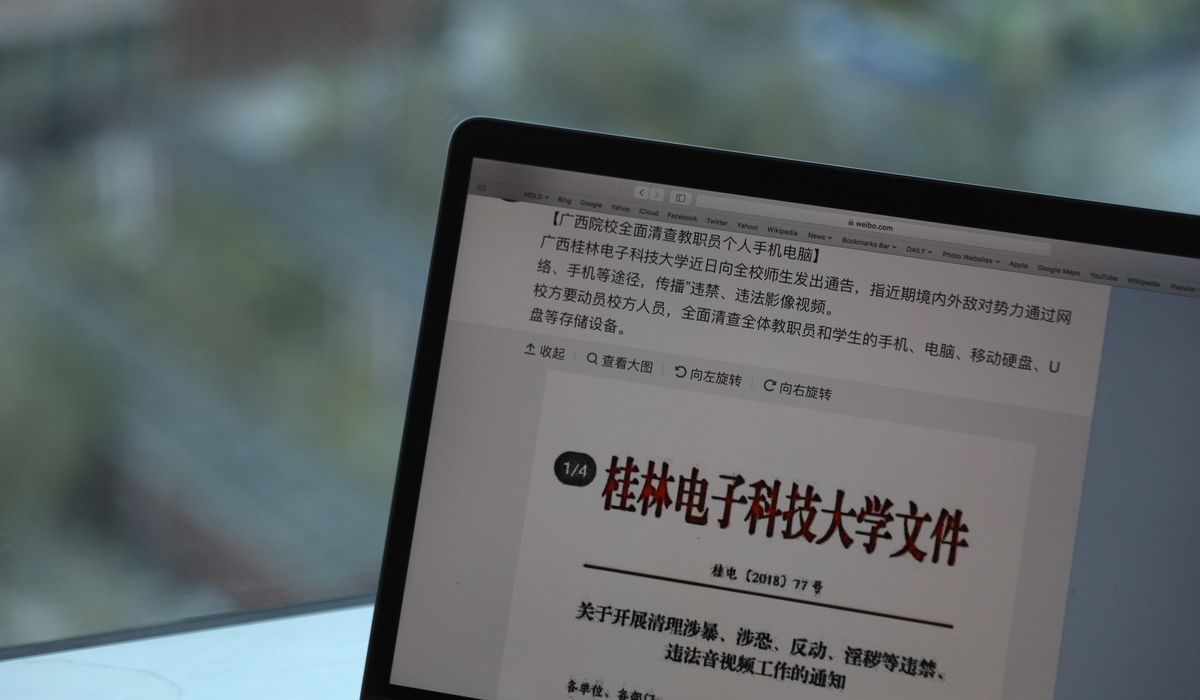

She said some Chinese Christians fear using a VPN because “if their cellphone is confiscated by the police, and if they knew that you install VPN to view overseas websites or banned content, they could get in trouble.”

The regime has been cracking down on religion throughout the administration of President Xi Jinping. Churches have been bulldozed and congregations closed. Nationals who administered websites for foreign religious groups have been called in for police interviews. The ethnic Uyghur residents of Xinjiang, a predominantly Muslim minority, have faced such severe repression and restrictions that U.S. government and human rights groups have labeled China‘s policies there “genocide.”

Levi Browde, executive director of the Falun Dafa Information Center in New York, said via email that “this new regulation is nothing new for us” because the movement’s practitioners in China have been subject to detention, imprisonment and even killing for communicating among themselves.

China’s crackdown on Falun Gong’s adherents has been particularly brutal, the group says, and has been widely condemned by human rights advocates.

Mr. Browde said “local, low-level officials sometimes look the other way or take measures into their own hands” to help the movement’s followers avoid persecution “because they are sympathetic and understand the unjust nature” of the government’s policies.

“In these cases, these new restrictions could make it more difficult for local officials to do that, and thus the overall impact could be an intensification of persecution,” he said.

One U.S.-based Christian ministry, which did not wish to be named, moved its extensive collection of Chinese-language sermons and teaching resources to servers outside of China once its local web administrator was summoned for a “conversation” with local police officials.

A State Department spokesperson, in an email to The Times, called China’s communist government “among the worst abusers of religious freedom in the world.”

The spokesperson said the U.S. urges China’s “government to uphold its international commitments with respect to the right to freedom of religion or belief for all individuals, including members of ethnic and religious minority groups and those who worship outside of official state-sanctioned institutions, including at unregistered churches, temples, mosques and other places of worship. Also, we urge the PRC government to uphold the promises made in its own constitution to protect the ‘freedom of religious belief.’”

The Times also reached out to the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association but received no immediate comment.