The final buzzer sounded at the Tokyo Olympics, the gold medal for the U.S. was won and Gregg Popovich held his emotions in check for at least a couple of minutes.

He shook hands with France coach Vincent Collet. He consoled some of the French players who had to settle for silver. His expression barely changed.

And then he walked across the court, to a small group of people in the first couple rows of the stands. That’s when the emotions began to flow, when he embraced a group that included Ime Udoka, Will Hardy, Chip Engelland and Jeff Van Gundy. The people who gave up their summer, quietly, to help him out.

“I’m still smiling,” Popovich said.

Relationships matter to Popovich more than the wins.

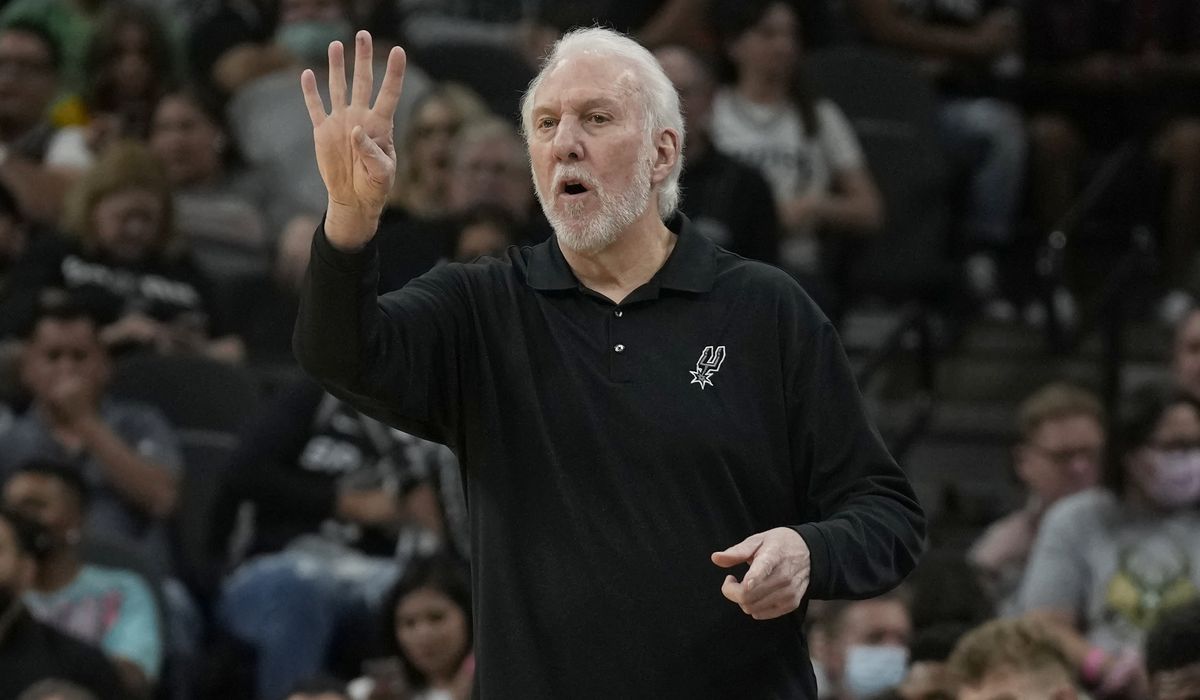

That is why he’s still coaching. And if Popovich knows how much longer he’ll coach, he’s not saying. But the final chapter of his coaching life is coming. He turns 73 in January. He’s in his 26th season on the San Antonio Spurs sideline. He has faced 158 different coaches in the NBA, or roughly half of anyone who has coached in the league’s 75 seasons.

His resume has no end. He is a five-time NBA champion, coach of an Olympic gold medalist and someone who will be a Basketball Hall of Famer after he retires — an honor he doesn’t want until after he is done coaching. And this season, the oldest coach in the league is leading one of the youngest rosters he’s ever had.

All that said, if anything, the gold medal didn’t leave Popovich thinking there was no stone left to turn. It seemed to reinvigorate him.

“We were proud, we wanted to do it for him and help him do it,” said Udoka, now in his first season coaching the Boston Celtics. “And so, to see the relief and get that monkey off his back, so to speak, it was a great time for all of us. So many hours spent behind the scenes, grinding away and trying to figure out how to make that team the best.”

Udoka is an example of how deep the ties run in Popovich’s very small circle of trust. When Udoka got hired by the Celtics, Popovich said he’d understand if Udoka left his role with the U.S. team to go focus on the new task in Boston.

Udoka had a staff to hire, summer league to oversee, roster decisions to help make. Popovich didn’t want to stand in the way of any of that. Udoka didn’t need long to recommit to the U.S. team.

“For me, it was a no-brainer,” Udoka said.

Hardy could have found other things to do this summer. Engelland and Van Gundy, too. So could the likes of Miami’s Erik Spoelstra, Gonzaga’s Mark Few and Orlando’s Jamahl Mosley, all of whom were part of the U.S. camp in Las Vegas and were in every meeting with Popovich before the team left for Japan.

They all chose to be part of Team USA, or perhaps more specifically, Team Pop.

“They did a great job in a very difficult situation,” said Charlotte coach James Borrego, another former Popovich assistant.

Popovich is a U.S. Air Force Academy graduate, considered a career as a spy, tried out for — and by some accounts, should have made — the 1972 U.S. Olympic team, speaks out often on political issues. The games this summer mattered more than he let on.

“I don’t think Pop has ever felt the pressure that he felt to go get this done for our country,” Borrego said. “Wearing that USA across his chest, he felt a real responsibility to produce, win a gold and put out a good product.”

It’s no different now with the Spurs. He just wants a good product.

In a season already with some major problematic storylines — the Kyrie Irving saga in Brooklyn, Ben Simmons’ mess of a relationship with Philadelphia, Enes Kanter speaking out on political matters and adding to the complexity of the ties between the NBA and China — San Antonio is doing what it does: just playing the game while avoiding messy situations.

Nobody is picking them as a title contender this season, which is fine with Popovich. He doesn’t mind that in a league where superstars rule, the Spurs have no superstars. They’ll play fast this season and they’ll play simple. He says he’s going to enjoy coaching a team like that.

“Pop stays the course,” Borrego said.

He’s still enjoying what he does, still on the Olympic group text where he and everyone who helped him out this summer talk just about every day, someone without fail mentioning the gold medal. He loves coaching Josh Primo, the 18-year-old who was born almost a decade into Popovich’s coaching career. The game, to him, is still fun.

“It’s exciting as hell,” Popovich said.

In other words, just like in Tokyo, he’s still smiling — and still coaching.