America and its allies are scrambling to establish a global infrastructure funding mechanism to counter the trillions of dollars China has spent to build projects and buy influence through what U.S. officials describe as Beijing‘s “mercantilist” and “predatory” Belt and Road development lending initiative.

While the Biden administration is framing its efforts as a push to counter climate change, it has generally run with momentum that former President Donald Trump set in motion to compete with the flood of infrastructure loans China has been offering to low- and middle-income countries around the world over the past decade for new roads, bridges, ports and rail lines.

The current White House says the future U.S. economy will depend heavily on the global appetite for infrastructure development, and that Washington‘s ability to steer funding toward such infrastructure is going to shape how much influence America has as a superpower over the coming decades.

If Washington wants to ensure the security of U.S. global supply chains and public health infrastructure going forward, it must play a more aggressive role in drumming up the estimated $40 trillion the developing world is estimated to need for infrastructure projects by 2035, said White House National Economic Council Director Brian Deese.

Mr. Deese, who spoke during a Peterson Institute for International Economics event last week, said U.S. engagement overseas can foster new economic and export opportunities for American companies that ultimately create jobs at home. An opportunity is at hand, he claimed, to “build areas of industrial-strength, manufacturing capability [and] innovation potential in the United States, while also providing an alternative to the mercantilist approach of the Chinese government.”

So far, the Biden administration‘s effort has been pinned to the announcement four months ago by the U.S. and others in the Group of Seven industrial democracies of a new pro-transparency infrastructure funding paradigm called the “Build Back Better World” or “B3W” initiative.

“This is not just about confronting or taking on China,” a senior White House official told reporters on background of the initiative upon its announcement in June. “This is about providing an affirmative, positive, alternative vision for the world than that [being] presented by China and, in some similar ways, but also in some different ways, Russia.”

The U.S. and other democracies have struggled for years to come up with ways to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which the communist government in Beijing rolled out nearly a decade ago as a springboard for its rising global influence.

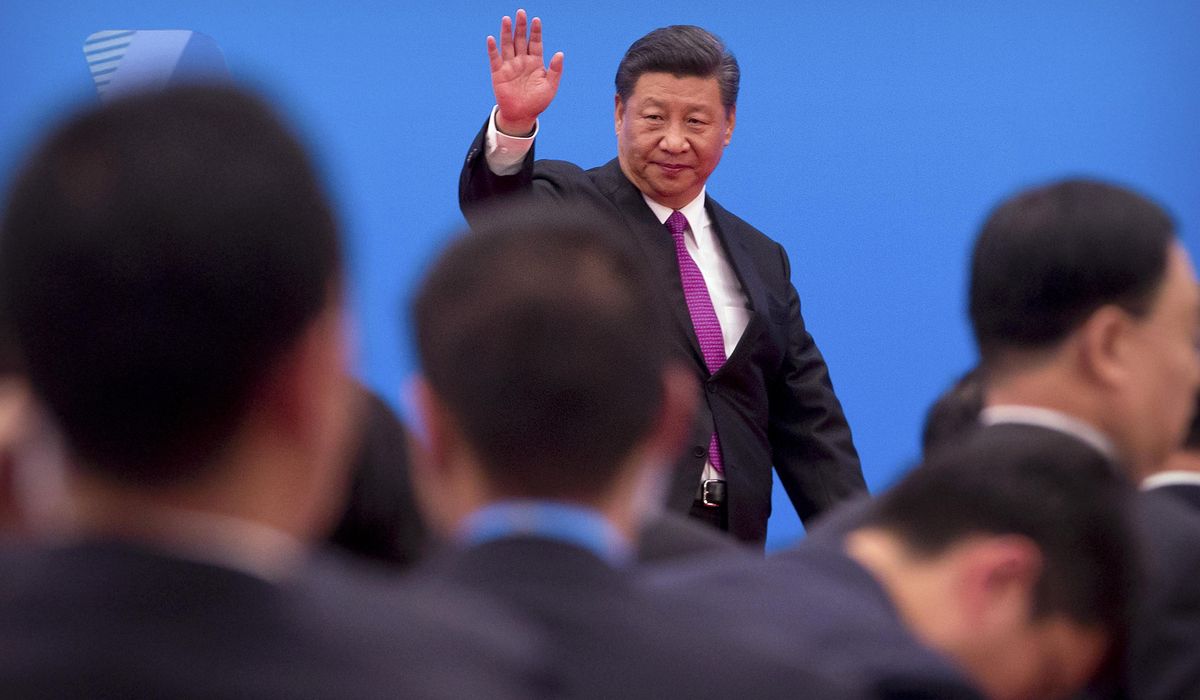

President Xi Jinping has described the program he first outlined in 2013 as an essential part of his “China dream” of a rise to economic superpower status. Many in Beijing also see it as the renewal of ancient, Chinese-centered trade routes such as the Silk Road through Asia and the Middle East that were cut off when first Europe and then the U.S. dictated world trade flows.

A Council on Foreign Relations survey earlier this year detailed the sweep of the Belt and Road project already: “Thirty-nine countries in sub-Saharan Africa have joined the initiative, as well as 34 in Europe and Central Asia, 25 in East Asia and the Pacific, 18 in Latin America and the Caribbean, 17 in the Middle East and North Africa, and six in South Asia. These 139 members of [the Belt and Road Initiative], including China, account for 40% of global GDP.”

Belt and Road has worked around the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, the bulwarks of the Western postwar economic order that were long the standard-bearers of global infrastructure financing prior to China’s arrival on the stage.

Chinese officials say the projects are win-win propositions, earning goodwill in countries across Southeast Asia, Europe, Africa and Latin America while generating construction projects for Chinese firms and infrastructure to create new trading routes and export opportunities. The biggest projects include roads and bridges, power plants, rail lines, fiber-optic networks and port overhauls.

U.S. officials and some private analysts have argued that Belt and Road involves “predatory” lending designed to ensnare poorer countries so China can later wring political and natural resource concessions in exchange for debt relief. Critics have even accused China of using the Initiative as cover for a multidecade strategy of laying the foundation for overseas military bases.

Beijing sharply rejects the accusations and regularly asserts that it is the U.S., not China, that has a history of militarizing foreign aid.

‘Hidden debt’

With regard to financial murkiness, however, a recent study by AidData, a research outfit at the Virginia-based College of William & Mary, found that Belt and Road is based on a “secretive overseas development finance program” that has saddled dozens of developing countries with nearly $400 billion worth of “hidden debt.”

Some 35% of the more than 13,000 projects financed by Chinese government loans have also featured “major implementation problems,” including corruption scandals, environmental hazards, labor violations and public protests, the study claimed. It added that Belt and Road is based on loans that often feature heavily conditioned liabilities that go undisclosed to borrowing nations in Africa, Southeast Asia and other corners of the world.

Furthermore, it said Beijing has “contractually obligated overseas borrowers to source project inputs (like steel and cement) from China” while “allowing countries to secure and repay loans with the money they earn from natural resource exports to China.”

The AidData study also said the U.S. and its allies are now “coalescing” around their own “B3W” infrastructure initiative, to be guided by “the principles of sustainable and transparent financing, good governance, public sector mobilization of private capital, consultation and partnership with local communities, and strict adherence to social and environmental safeguards.”

The G-7 nations — the U.S., Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United Kingdom — announced the B3W initiative in June, taking the name from President Biden’s centerpiece economic program in his 2020 presidential campaign.

But it remains to be seen whether the Biden administration has the geopolitical capital to steer it toward actual results. Also unclear is the extent to which B3W will coordinate with other initiatives already aimed at countering China, including the diplomatic and security alignment of the “Quad” countries — the U.S., India, Japan and Australia.

The U.S., Japan and Australia already announced two years ago the so-called “Blue Dot Network,” a transparency initiative aimed at assessing and certifying infrastructure development projects in Indo-Pacific and beyond. The Trump era also ushered in a revamped U.S. International Development Finance Corporation aimed at triggering bigger private investments in foreign development projects. Mr. Trump separately instituted the so-called “Economic Prosperity Network” in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce global supply chain reliance on China.

Biden administration officials suggest B3W will harness all of the previously announced initiatives into a coherent, complementary whole.

“We are looking to transform our U.S. government financing tools to leverage the full scale of private capital into this effort,” Mr. Deese said last week. “Just to give you an example, the Development Finance Corporation — the newly reconstituted DFC — has just this year innovated in entering into new tools to try to unlock private capital.”

He pointed to the DFC’s role in a recent “debt swap” in Latin America that resulted in a $250 million investment in a Brazilian “smart city infrastructure” company.

However, Mr. Deese also appeared eager to present B3W as being just as much about countering climate change as it is about countering China. Its goal, he said, is to push a “multilateral” approach that encourages a “race to the top” among influential nations toward “investing in a highroad, low-carbon way that puts workers and worker rights at the center of our efforts.”

He suggested the B3W push had a role in China‘s recent announcement that it will no longer build or finance coal-fired power plants internationally. “It was a welcome sign, and this also follows shortly after equivalent commitments by South Korea and Japan, and if you step back, those two countries, along with China, have accounted for more than 95% of total foreign investment in coal-fired power plants since 2013,” Mr. Deese said. “Part of the effort of bringing a multilateral approach to Build Back Better World is to encourage more positive, highroad activity, from other countries as well.”

“None of this is going to be easy. If it was, a lot of this would have been done already,” he said.

Some observers argue the U.S. and Western push may could end up competing positively — or even cooperating — with China‘s development spending in the long run.

“The idea is to turbocharge U.S. and Western development finance in an explicit counter to Beijing — not frontally,” longtime geoeconomics journalist Keith Johnson wrote recently in Foreign Policy.

“The B3W, as it is known, focuses on a few core areas — climate change, health security, digital connectivity, and gender equity — that don’t exactly go toe-to-toe with China dredging harbors or hewing highways out of mountainsides,” Mr. Johnson wrote. “…With Washington and Brussels now fully mobilized to counter China’s overseas investments, the question becomes: Can the West — with dueling infrastructure programs having different rubrics and priorities — cooperate, or will there be an uncoordinated tag team facing China?”