Wow, was I ever wrong.

On Jan. 16, 2010, I reported that “a nationwide survey last year found that investors expect the U.S. stock market to return an annual average of 13.7% over the next 10 years.” That was ridiculous, I sneered: “What are we smoking, and when will we stop?” I thought 6% would be generous, adding that “faith in fancifully high returns” amounted to “fairy-tale expectations.”

Over the 10 years ended Dec. 31, 2019, the S&P 500 returned 13.6%—almost exactly what those investors I mocked had expected. With stocks near record highs today, what should you and I learn from my mistake?

I didn’t foresee how fracking and cloud computing would turbocharge the economy or how a decade of rock-bottom interest rates would make many investors feel there is no alternative to stocks. Nor did I anticipate the 2017 corporate tax cuts that unleashed stock buybacks, pouring money into investors’ pockets.

I also made a more basic mistake: relying too mechanically on the past in estimating the future.

Robert Shiller, a finance professor at Yale University, who won a Nobel Prize in economics in 2013, measures how expensive stocks are by taking the price of the S&P 500 index, dividing by the average of its past 10 years of earnings and adjusting both the price and the earnings for inflation.

The gauge is known as the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio, or CAPE. And, by that yardstick, stocks were priced at 20.3 times their adjusted long-term profits at the beginning of 2010. The average valuation for U.S. stocks over the full historical sweep of Prof. Shiller’s data, all the way back to 1881, was then 16.3 times their adjusted earnings.

That meant that stocks were priced nearly 25% above their historical average. This led me to believe their returns over the coming decade were bound to be lower.

Over the next 10 years, earnings boomed, but the price investors were willing to pay for those earnings boomed even more.

Today, at a CAPE of 37.1 times adjusted earnings, stocks are significantly above their early record of 32.6 in September 1929 and not far from their all-time high of 44.2 in December 1999.

Both peaks ushered in devastating bear markets, with stocks losing more than 80% between 1929 and 1932, and more than 40% between the end of 1999 and late 2002.

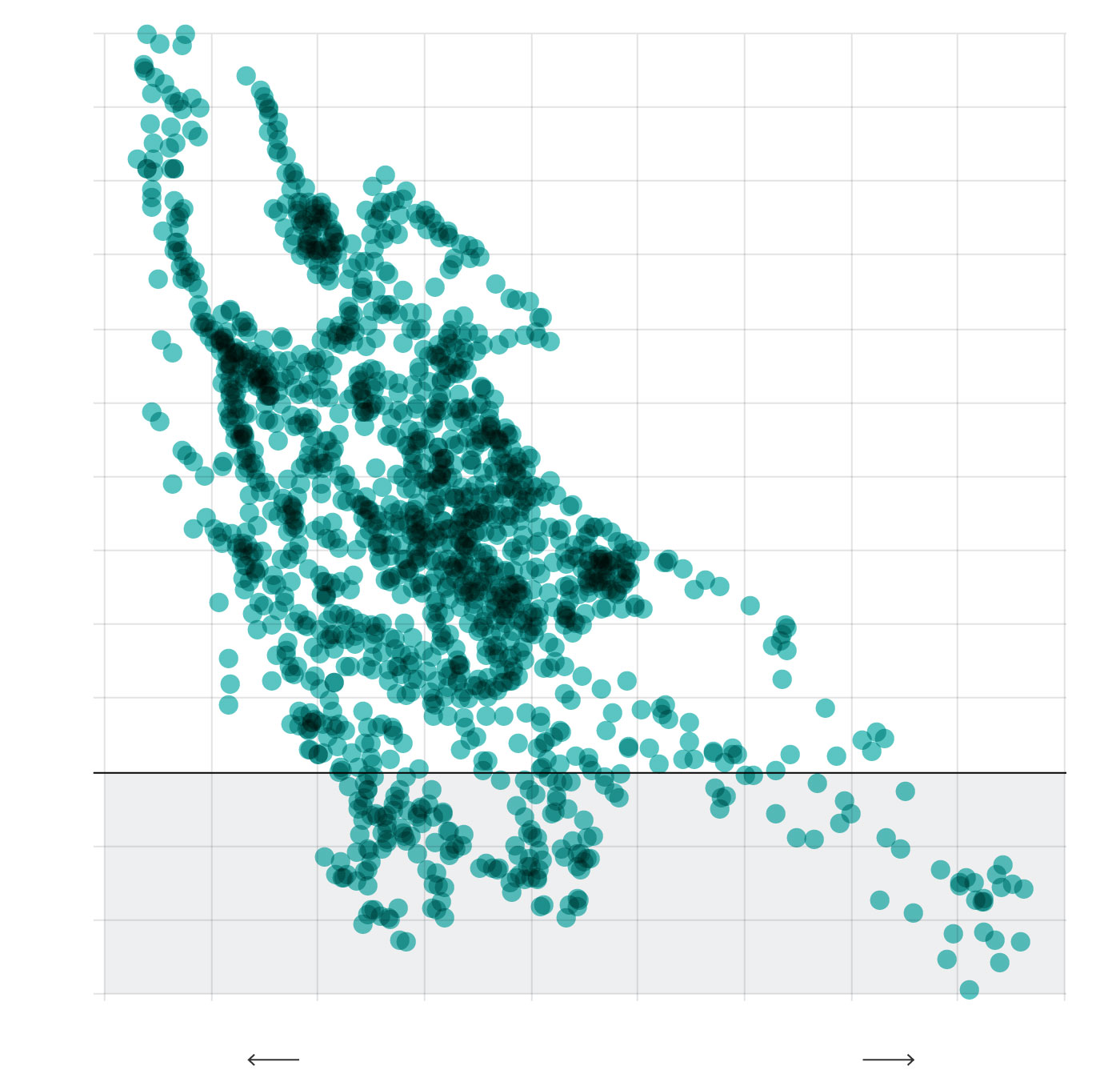

Pay More Now, Earn Less Later

On average, when stocks are more expensive, their future long-term returns tend to be lower.

Subsequent 10-year total returns, adjusted for inflation

10-year total return, annualized

Cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio*

Less expensive

more expensive

10-year total return, annualized

Less expensive

more expensive

Cyclically adjusted

price/earnings ratio*

10-year total return, annualized

Less expensive

more expensive

Cyclically adjusted

price/earnings ratio*

Many analysts and asset managers are warning that today’s market is flashing a red alert. The respected investor Jeremy Grantham recently wrote that U.S. stocks and other assets are so overpriced that they constitute a “superbubble,” setting up “the largest potential markdown of perceived wealth in U.S. history.”

History isn’t a tape measure, though. You can’t just lay the past onto the present and declare that it gives you an unambiguous basis for a drastic decision, like slashing your exposure to U.S. stocks.

The past isn’t a constant; it’s in constant flux. Economists and investors often say that stock valuations should “regress to the mean,” or move away from extreme highs or lows back toward the long-term average. But that historical average is continuously being modified by new results.

Twenty years ago, in January 2002, the average CAPE ratio in Prof. Shiller’s database, measured across all the years back to 1881, was 15.8 times earnings. Back in mid-1982, the CAPE was 14.7 times earnings over its full history.

At the end of last month that average, back to 1881, had risen to 17.3.

So which mean valuation should stocks regress to?

Less than 15 times earnings? More than 17?

Or could the mean keep rising if corporate taxes stay low, interest rates remain moderate and new technologies keep transforming society?

“The problem is, we don’t know,” says Prof. Shiller with a dry laugh.

Another problem: We don’t have as much of the past as it seems. Prof. Shiller’s 10-year averages begin in 1881, providing only 14 nonoverlapping 10-year periods (1881 to 1890, 1891 to 1900, 1901 to 1910, and so on).

What feels like such a long historical vista, then, is a small sample, full of noise. Yes, on average, stocks have delivered low future returns for 10-year stretches after their CAPE valuation was high, and superior performance after periods of low valuation—but not always.

Had you bought stocks in early 1996, when the CAPE ratio was two-thirds higher than its historical average at the time, you still would have earned a 4.9% annualized return, after inflation, over the next 10 years. Counting dividends and share repurchases, your annualized return net of inflation would have been a robust 6.6%, according to Prof. Shiller’s data.

CAPE provides “a limited number of observations, but that’s the world we live in,” says Prof. Shiller. “We’re constantly moving into a new era. The world changes qualitatively all the time, so we’re not ready to rely exclusively on ratios.”

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How do you expect the stock market to perform over the next decade? Join the conversation below.

Even at today’s elevated CAPE, says Prof. Shiller, “I’ve never recommended that people sell everything. You might cut somewhat back on U.S. stocks, tilt toward international stocks, or move to cheaper sectors” such as financials, healthcare or consumer staples.

Over the past few years, Prof. Shiller has “tilted down” his exposure to U.S. stocks, but “not totally,” he says. “I still have hopes that the American stock market will do really well.”

Trimming your stocks a bit as they rise always makes sense. But dumping all your shares because they are near record highs makes sense only in a world of perfect certainty—which exists nowhere but in fairy tales.

Write to Jason Zweig at [email protected]

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8