Ask what the single best investment is likely to be this year, and you might get suggestions like bitcoin, Tesla Inc. TSLA -3.54% shares or cheap value stocks.

I think the best investment of 2022 is likely to be discipline. With the course of the coronavirus pandemic unclear, inflation expected to keep spiking and the Federal Reserve poised to raise interest rates, anything can happen—and probably will.

What’s more, the things that feel most certain aren’t as obvious as they seem—so investors need to beware of taking drastic actions that, later on, they will wish they could undo.

To see why discipline is such an important investing virtue, consider the history of interest-rate decisions by the Fed. The central bank appears to be projecting at least three 0.25% increases in interest rates this year, potentially starting in March. Most investors are treating that forecast as a foregone conclusion.

It isn’t. Go back to the 1990s and you’ll see that the central bank has sometimes raised or lowered rates in ways that not only have taken markets by surprise, but contradicted the Fed’s own expectations. Investors who overhaul their portfolios based on what the Fed seems likely to do could get stranded if it does something else entirely.

Or consider that stocks feel as if they must be due for a setback. That’s no sure thing, either.

The S&P 500 returned 28.7%, counting reinvested dividends, last year—the seventh-highest gain in the past half-century, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. That came after total returns of 18.4% in 2020 and 31.5% in 2019. In the past three calendar years, U.S. stocks have doubled.

Flying High

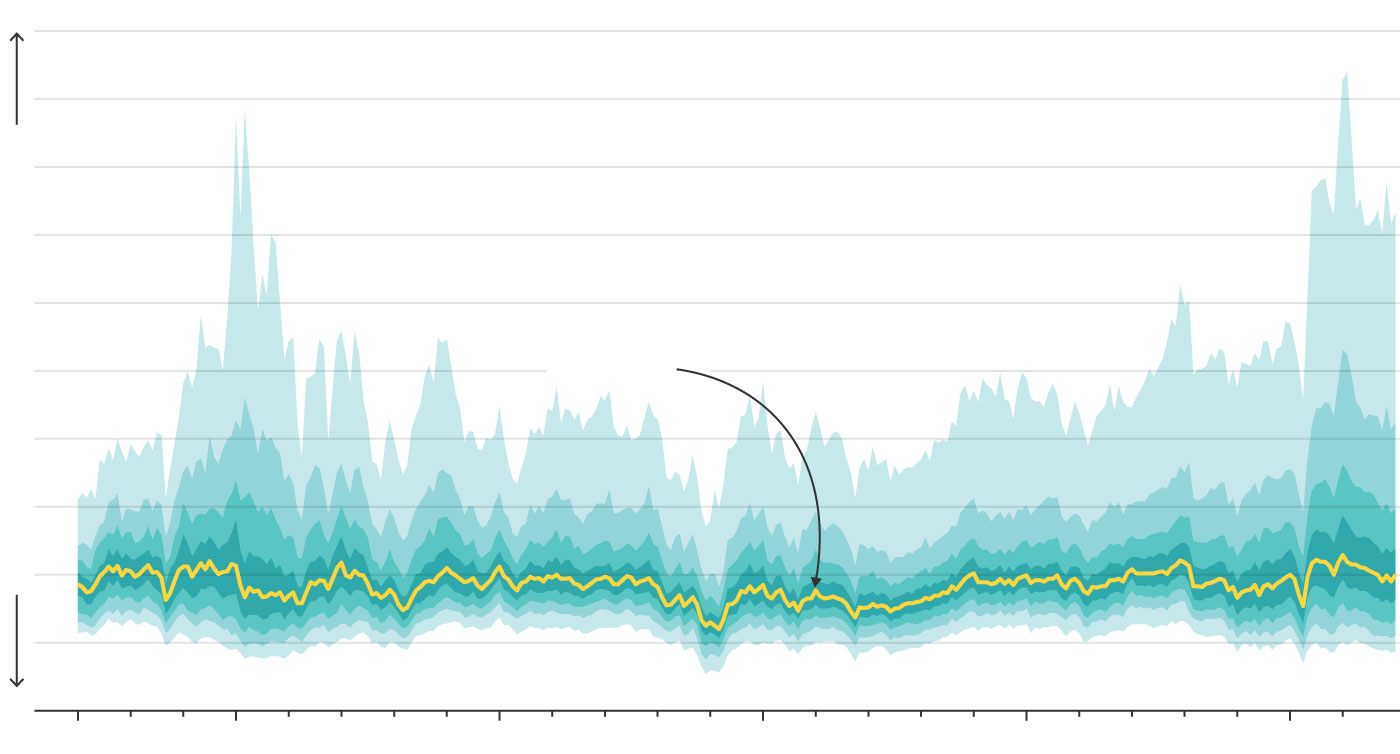

While the typical stock isn’t cheap, the most expensive stocks are at their highest prices in decades.

Price/earnings ratios of U.S. stocks based on expected earnings, by deciles from highest to lowest P/E

more expensive

less expensive

more expensive

less expensive

more expensive

less expensive

So it’s no wonder Wall Street’s strategists almost unanimously expect tepid returns in 2022—or that the year is already off to a hesitant start, as fears of rising interest rates nicked 1% off stock prices this week.

You’re wrong if you think big gains can never recur after three years in a row. In 1995, the S&P 500 returned 37.5%. In 1996, stocks went up 23.1%. They gained 33.3% in 1997, 28.7% in 1998 and still another 21.1% in 1999.

Markets finally crashed in 2000. Over the next 2½ years, the S&P 500 fell nearly 50% and the Nasdaq-100 index of technology stocks lost more than 80%.

But that reckoning came long after many market commentators—including me—had expected. As the money manager Martin Zweig (no relation), who died in 2013, liked to say: “The markets will always do whatever they have to do to screw over as many people as possible.”

All this explains why discipline is the greatest investing virtue. When you drastically change your long-term course based on what feels like a short-term sure thing, you’re likely to end up caught by surprise—and racked with regret.

Investors are always searching for good ideas, when what they need are good habits. Only procedures that you repeat and follow until they become automatic will enable you to invest steadily over the long run.

“Your behavior is much more controlled by what’s easy in your environment than most of us think,” says Wendy Wood, a professor of psychology and business at the University of Southern California and author of the book “Good Habits, Bad Habits: The Science of Making Positive Changes That Stick.”

To block bad habits, Prof. Wood’s research shows, you need to add “friction,” or restraints that turn easy, automatic behaviors into actions that require effort.

If you find yourself constantly checking your portfolio on a brokerage app like Robinhood, set your phone to grayscale, which will neutralize the visual excitement that can goad you into overtrading. If that doesn’t work, move the app off your phone’s home screen—or delete it, so you can use it only by walking to your computer.

If you must watch CNBC or other financial television, watch it with the sound turned off.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

What strategies do you use to prevent yourself from making rash investment decisions? Join the conversation below.

“One of the really nice things about adding friction to a behavior,” says Prof. Wood, “is that it encourages you to do something else.” Making a bad habit harder to engage in enables you to replace it with a good habit.

After decades of investing, Rashmi Doshi, a 69-year-old retired telecommunications executive in the San Diego area, regularly monitors his portfolio only four times a year. Each time he prepares his estimated quarterly income taxes, Mr. Doshi uploads his investment account values into a spreadsheet. There, he checks their returns over the prior three months and the past one, three and five years.

If any holding has moved at least 5% outside the target Mr. Doshi has set for it, he either buys or sells as needed to get it back in balance. More often than not, he does nothing. “Most of the gyrations are just noise,” he says, “and as a radio-frequency engineer, I’m used to dealing with noise.”

The key to discipline? Think of investing not as a series of decisions, but as a habit.

Write to Jason Zweig at [email protected]

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8