Thais Perkins is the owner of Reverie Books in Austin, Texas, and the parent of a middle school student and high school student. Among the books she is eager to have in her store, and in the schools, is an expanded edition of “The 1619 Project” that comes out this week.

“My store is a social-justice oriented bookstore, and this book fits very well within that mission,” she says. “I am promoting community sponsorships of the book, where people can purchase a copy and have it donated to one of the schools.”

That is assuming, of course, the school will be allowed to accept it.

The “1619 Project,” which began two years ago as a special issue of The New York Times magazine, has been at the heart of an intensifying debate over racism and the country’s origins and how they should be presented in the classroom.

The project has been welcomed as a vital new voice that places slavery at the center of American history and Black people at the heart of a centuries-long quest for the U.S. to meet the promise – intended or otherwise – that “all men are created equal.” Project creator Nikole Hannah-Jones received a Pulitzer Prize for commentary.

At the same time, opposition has come from such historians as the Pulitzer Prize winner Gordon Wood, who denounced the project’s initial assertion that protecting slavery was a primary reason for the American Revolution (the language has since been amended) and from Republican officials around the country. Sen. Tom Cotton, of Arkansas, has proposed a bill that would ban federal funding for teaching the project, and the Trump administration issued a “1776 Commission” report it called a rebuttal against “reckless ‘re-education’ attempts that seek to reframe American history around the idea that the United States is not an exceptional country but an evil one.”

In 2021, Republican objections to the 1619 project and to critical race theory have led to widespread legislative action. According to Jonathan Friedman, director of free expression and education at PEN America, dozens of bills around the country have been proposed or enacted that call for various restrictions on books seen as immoral or unpatriotic. Two bills passed in Texas specifically mention the 1619 project.

“When you look at the current movement about critical race theory, you can see some of its origins in the fight over the 1619 project,” Friedman says.

The Texas laws, Friedman says, are “opaque” about how or whether a given school such as the ones attended by Perkins’ kids could receive a copy of the 1619 book. He cites a passage which reads “a teacher, administrator, or other employee of a state agency, school district, or open-enrollment charter school may not … require an understanding of the 1619 Project.” The provision “effectively bars a teacher from teaching or assigning any materials from the 1619 Project,” he says, but not the school library from stocking it – especially if the book has been donated.

A spokesperson for the Austin Independent School District says in a statement that the “academics team is currently working on this internally, and we are not yet able to speak to the issue.”

The 1619 book appears destined for political controversy, but it’s also a literary event. Contributors range from such prize-winning authors on poverty and racial justice as Matthew Desmond, Bryan Stevenson and Michelle Alexander, to Oscar-winning filmmaker Barry Jenkins, to “Waiting to Exhale” novelist Terry McMillan and author Jesmyn Ward, a two-time winner of the National Book Award for fiction. Along with essays on religion, music, politics, medicine and other subjects, the book includes poetry from the Pulitzer winners Tracy K. Smith, Yusef Komunyakaa, Rita Dove and Natasha Trethewey.

“It’s just such an amazing part of this book,” Hannah-Jones says of the poems and prose fiction. “It gives you these beautiful breaks between these essays.”

“The 1619 Project” book already has reached the top 100 on the bestseller lists of Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble.com. Online seller Bookshop.org has set up a partnership with the publisher One World, an imprint of Penguin Random House, for independent stores such as Reverie Books to donate copies to local libraries, schools, book banks and other local organizations.

Hannah-Jones’ promotional tour is a mix of bookstores and performing venues, and at least one very personal journey. She will make appearances at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the Free Library of Philadelphia. She will visit Waterloo West High School in her home state of Iowa, partner with Loyalty Bookstore and Mahogany Books for an event at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington and attend the Chicago Humanities Festival.

She also will speak at the annual convention of the National Council of Teachers of English. Lynsey Burkins, who leads the council’s Build Your Stack initiative, which helps teachers build their classroom libraries, says it was important to reflect a diversity of experiences in the classroom texts. Burkins, a third grade teacher in Ohio, says that it’s easier to engage students with topics like history when they can see themselves in the work they’re reading.

“The more books that we have in our menu, the more that students get to start learning about historical events in a way that is humanizing for them,” Burkins says.

Hannah-Jones says that reaching classrooms was not on her mind when she conceived of “The 1619 project,” but that schools have become important outlets. Through a partnership with the Pulitzer Center, which has teamed with the Times before, the project has been embraced by dozens of schools and educational centers around the country, from high school history faculty in Baltimore to grade school teachers in Ann Arbor, Michigan, to the advocacy group Texas Trailblazers for Equity in Education.

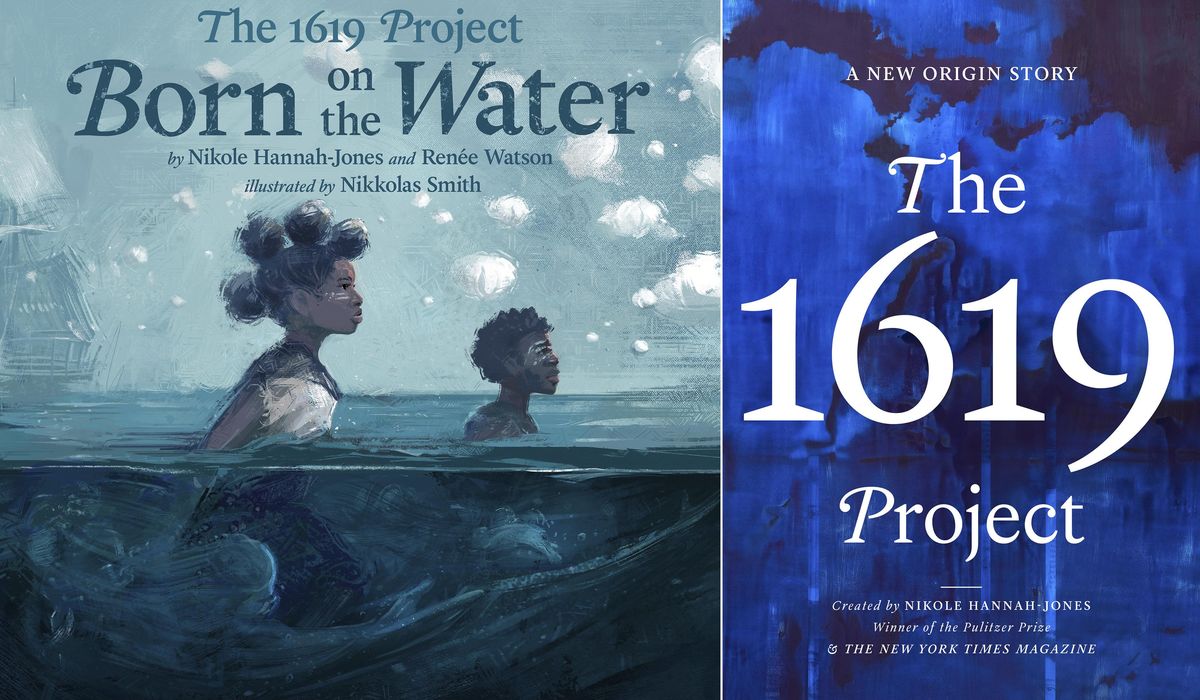

Hannah has a second book out this week. The Penguin Random House imprint Kokila is publishing the picture story “Born On the Water,” a collaboration among Hannah-Jones, co-writer Renée Watson and illustrator Nikkolas Smith that Hannah-Jones says she was inspired to work on after readers of the Times magazine asked for something addressed to younger readers.

It is a mini-history, with verse and images, that traces centuries of Black lives from their thriving communities in Africa to their forced passage overseas and enslavement to their hard-earned freedom. Those once “brokenhearted, beaten and bruised” became “healers, pastors and activists,” Hannah-Jones and Watson write, “because the people fought/America began to live up to its promise of democracy.”

Jess Lifshitz, who teaches fifth grade literacy in the Chicago suburbs, says that although she was familiar with “The 1619 Project,” she didn’t plan to directly incorporate the work into her classroom because of her students’ age. That changed when she received a preview copy of “Born on the Water.”

“It honors what children are able to wrestle with and grapple with, and I think so many books written for children underestimate what they’re capable of,” Lifshitz says. “With all the tension that is swirling around adults, sometimes it’s hard to remember what a beautiful picture book that tells an accurate story about history can do for the kids sitting in the room.”

___

This story has been updated to correct a quotation in the second paragraph to read “social-justice oriented” instead of “socially justice oriented,” and to add the word “up” in the quotation “America began to live up to its promise of democracy.”