The typical stock fund manager is a sheep in wolf’s clothing: passively mimicking the market, with only a few small and timid active bets.

By taking the opposite approach, Wilmot H. Kidd III has racked up one of the greatest long-term track records in the history of investing.

Over the past 20 years, Mr. Kidd’s Central Securities Corp ., a closed-end fund, has outperformed Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Over the past 25, 30, 40 and even nearly 50 years under Mr. Kidd, Central Securities has resoundingly beaten the S&P 500.

The keys to his success? Patience, concentration and courage.

On Dec. 31, Mr. Kidd, 80 years old, will step down as Central’s chief executive, although he will remain chairman. The fund has $1.3 billion in assets.

Don’t feel bad if you’ve never heard of Mr. Kidd. He has no LinkedIn page; barely even a photograph of him can be found online. He thinks my recent conversation with him is, at most, the fifth interview he has given in his half-century-long career.

But Mr. Kidd is a model for how to think about, and practice, intelligent investing.

In 1962, the business historian Alfred D. Chandler wrote that “unless structure follows strategy, inefficiency results.”

At most asset managers, strategy follows structure instead. As a result, funds own too many stocks, trade too frequently and charge too much.

No wonder most active managers underperform market-tracking index funds that charge a fraction of their fees.

At Central Securities, Mr. Kidd ensured that structure has followed strategy—with astounding results.

If you had invested $10,000 in Central Securities at the end of March 1974, when Mr. Kidd officially took over, you would have had nearly $6.4 million by the end of this October, according to the Center for Research in Security Prices. The same amount put into the stocks in the S&P 500 would have grown to $1.9 million. Central Securities grew at 14.5% annualized with dividends reinvested, versus 11.7% for the S&P 500 stocks.

That’s not to say Mr. Kidd has never underperformed. Over the past 10 years, according to Morningstar, Central has lagged the S&P 500 by an average of three percentage points annually as giant tech companies have raced ahead. (So far in 2021, Central is outperforming again.)

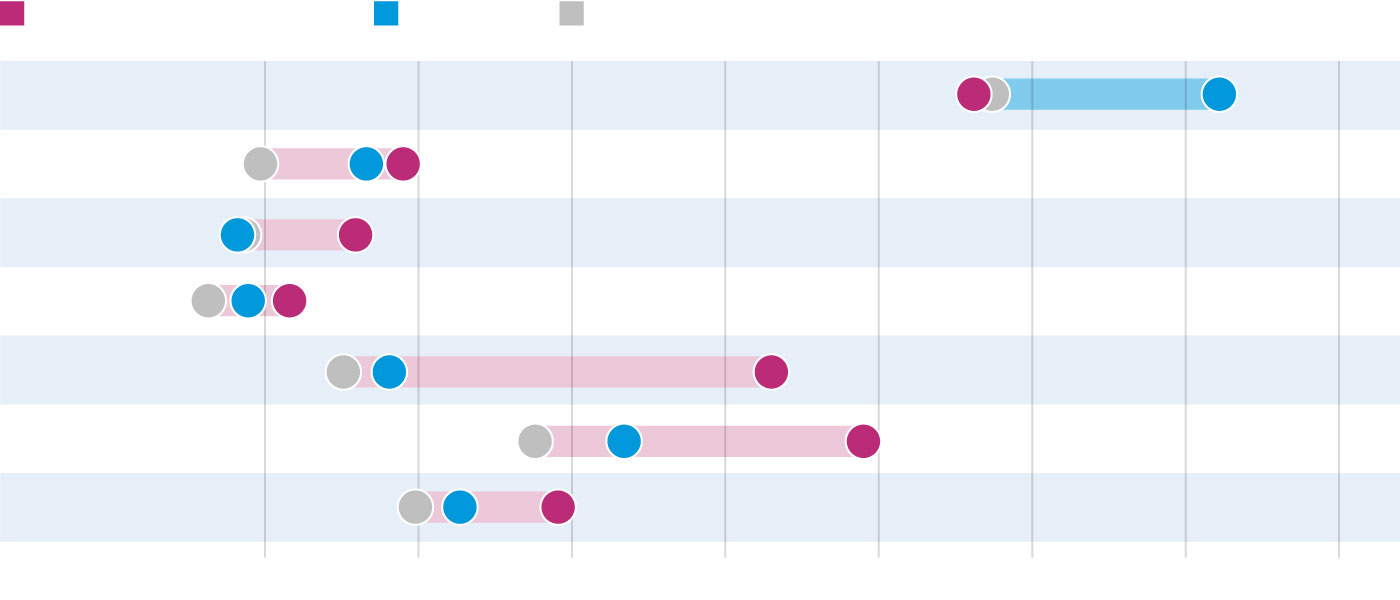

No Kidding

Central Securities Corp., a closed-end fund run by Wilmot Kidd, has beaten the market for remarkably long periods, faltering only a bit in recent years.

Annualized returns

Central Securities Corp.

Total U.S. stock market

Central Securities Corp.

Total U.S. stock market

Central Securities Corp.

Total U.S. stock market

The firm was founded in 1929 as a closed-end fund. In that structure, new investors buy shares from someone else—rather than from the fund itself. Cash doesn’t flood in when stocks are overpriced, nor do investors demand their money back from the fund during bear markets. That enables a closed-end fund to manage its portfolio, without having to manage its investors.

Central Securities is internally advised, meaning Mr. Kidd and his two co-managers, John Hill and Andrew O’Neill, work for the fund itself—not for a management company that charges the fund a fee. The fund’s expenses are running at 0.54% this year, far below the average at other closed-end or mutual funds. (Mr. Hill will become chief executive on Jan. 1.)

Mr. Kidd, his family and his family foundation own nearly 45% of the fund. “We’ve always said: We’re in business to make money for the stockholders, not off the stockholders,” he says.

Portfolio managers brag about being “long term” if they hold stocks for a year or so. Mr. Kidd makes those folks look like day traders. He has often held stocks for longer than many other portfolio managers have been alive. Central has owned Analog Devices Inc., its second-largest position, for 34 years. Mr. Kidd held Murphy Oil Corp. for more than four decades, from 1974 to 2018.

Over the past 15 years, Central’s annualized portfolio turnover rate has averaged 11%. That means it holds its typical stock for nearly a decade—roughly six times longer than the average active mutual or closed-end fund, according to Morningstar.

Owning stocks for years, rather than months, minimizes the costs of trading, reduces the burden of researching new holdings and enables Central to burrow deeply into understanding a business.

“We want to own growing companies during as much of their period of growth as we can,” says Mr. Kidd. That enables compounding to work its magic.

“It takes time to learn to live with an idea,” he says. “All these portfolio managers [who sell stocks within a year], I don’t believe they even know what they own.”

Another way Central’s structure follows Mr. Kidd’s strategy: The fund doesn’t hold tiny positions in hundreds of stocks. “We’ve always felt you had to concentrate,” he says. “You’ve got to have a few big positions, you’ve got to own a lot of what works.”

The average actively managed U.S. stock fund owns at least 160 stocks and has only a third of its assets in its top 10 holdings, according to Morningstar. Central has 33 positions, with fully 57% of its money in its 10 biggest.

Isn’t that risky? As Mr. Kidd wrote in his 1978 annual report, “Risk may be reduced through active and more intimate knowledge of the problems of companies in which we invest.”

Mr. Kidd’s bets aren’t merely big, but also bold: 22% of Central’s assets are in Plymouth Rock Co., a Boston-based auto and property insurer whose stock isn’t even publicly traded. Mr. Kidd met Plymouth Rock’s future founder, James Stone, when they both were working on Wall Street in the late 1960s. “He was very bright, and we stayed in touch,” says Mr. Kidd. In 1982, Central Securities became the first outside investor in Plymouth Rock, at an eventual total cost of $3.5 million; its remaining shares, which cost $700,000, are on the fund’s books for $293 million.

Plymouth Rock is one of several stakes Central took in private companies in the 1980s, the early days of private equity and venture capital, before such deals were flooded with buyers as they are today.

By structuring the fund to follow a strategy of making larger, focused bets on fewer companies, Mr. Kidd has taken advantage of sweeping long-term trends.

In the mid-to-late 1970s, Central earned gigantic returns investing in such companies as Murphy Oil, Cities Service Co. and Ocean Drilling & Exploration Co., which together peaked at about 30% of the portfolio.

But Mr. Kidd was also open to new ventures. Around 1969, he was a young investment banker at Hayden, Stone & Co. and helped draft a prospectus for a fledgling company called Intel Corp. Although Intel delayed its public offering until 1971, Mr. Kidd got to know its co-founders Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How is your investing strategy similar to Mr. Kidd’s? How is it different? Join the conversation below.

That led Central some years later to take sizable positions in several rising technology stars of the day, including stocks like Informatics General Corp. Through a small holding in a venture-capital fund, Central owned an indirect stake in Compaq Computer Corp., and Mr. Kidd noticed Plymouth Rock’s insurance agents using portable Compaq computers in the field.

“We could see that this was part of the revolution that Noyce and Moore started,” he says, “and that there was a serious business use for a portable computer.”

By 1982, Mr. Kidd decided the energy boom had mostly played out. Within a few years, Central had pivoted from having a third of its assets in energy to having a third in tech stocks—and earned big gains again.

When I ask Mr. Kidd if he attributes his long success to luck or skill, he lets out a long, quiet, dry laugh before saying something I don’t think I will ever forget: “Skill is just recognizing when you’ve gotten lucky.”

He explains, “It’s when you’ve been fortunate enough to make an investment in a great company, and suddenly you realize just how very lucky you were, and you buy more. That’s skill, I suppose. That—and holding on to what you have and not chickening out.”

Write to Jason Zweig at [email protected]

Copyright ©2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8