Insurers have been buying up privately issued bonds to earn higher yields in a low-interest rate world. Now, state regulators are demanding more information about these investments, which back many Americans’ life-insurance policies.

Starting in January, insurers will need to file details about the credit ratings for the privately issued bonds that they purchase. Regulators are concerned that the ratings potentially understate the risks of the securities.

Regulators also will examine how well the current ratings process works to protect against losses. They will consider changes ranging from requiring multiple ratings for each bond to dropping some ratings firms, regulatory documents show. The regulators are working through the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, a standard-setting group for the state-regulated industry.

Low interest rates have made it hard for insurers to earn profits on some types of policies and annuities. That has led many to sell these businesses to private-equity, asset-management and other financial firms. The buyers believe they can turn healthy profits using their investment savvy, along with operating differences.

In particular, newcomers have favored privately placed debt and asset-backed securities, including collateralized loan obligations, according to A.M. Best Co., which rates insurers for claims-paying ability. These securities typically yield more than traditional corporate bonds and other widely held investments because they can be harder to sell.

Now, the NAIC is trying to determine whether the bonds themselves are riskier than their ratings indicate. If so, that could mean unexpected investment losses for insurers.

Credit-ratings firms play an important role in the insurance industry, which is one of the biggest buyers of bonds and loans to businesses and governments. Ratings determine how much capital insurers must set aside in case bonds aren’t paid back.

The relationship between state regulators and ratings firms has been fraught at times. After supposedly safe mortgage-backed bonds lost value in the financial crisis, the NAIC hired financial-modeling specialists to judge the risk of the securities. Loss estimates are currently calculated by asset manager BlackRock Inc., rather than the credit-ratings firms.

Ratings firms say they have improved their corporate governance, analyses and compliance processes since the crisis. One thing that hasn’t changed is a conflict of interest that is inherent in their business model: In general, the firms are paid by the companies whose bonds they rate. Companies have incentives to hire the firms that give them the highest ratings because it means a lower cost to borrow.

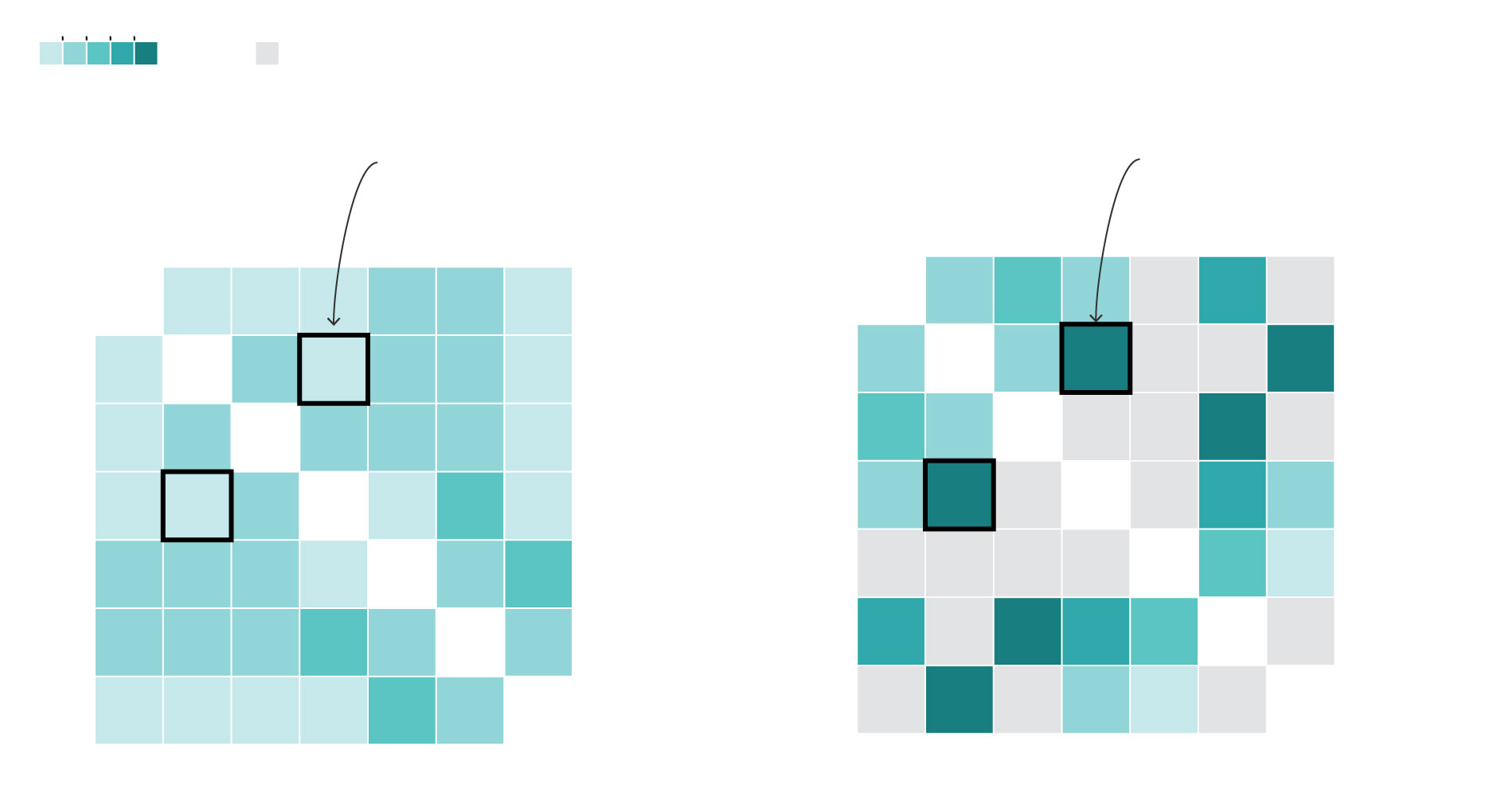

Average disparities between ratings providers tend to be wider for privately rated bonds than publicly rated, according to a study by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

Not available*

On average, ratings firms B and D show a roughly one-notch difference—say, from A1 to A2—on ratings disclosed publicly.

On securities rated privately, firms B and D on average differ by five notches—say, from A1 to BBB3.

Publicly rated bonds

Privately rated

RATINgs FIRMS

RATINgs FIRMS (names withheld by study)

average rating difference

Not available*

On average, ratings firms B and D show a roughly one-notch difference—say, from A1 to A2—on ratings disclosed publicly.

On securities rated privately, firms B and D on average differ by five notches—say, from A1 to BBB3.

Publicly rated bonds

Privately rated

RATINgs FIRMS

RATINgs FIRMS (names withheld by study)

average rating difference

Not available*

On average, ratings firms B and D show a roughly one-notch difference—say, from A1 to A2—on ratings disclosed publicly.

Publicly rated bonds

RATINGS FIRMS

RATINgs FIRMS (names withheld by study)

On securities rated privately, firms B and D on average differ by five notches—say, from A1 to BBB3.

Privately rated

average rating difference

Not available*

Publicly rated bonds

On average, ratings firms B and D show a roughly one-notch difference—say, from A1 to A2—on ratings disclosed publicly.

RATINgs FIRMS (names withheld by study)

Privately rated

On securities rated privately, firms B and D on average differ by five notches—say, from A1 to BBB3.

Now regulators are especially concerned about the ratings on private securities, which don’t trade publicly and are often held by a small number of investors. More than 5,000 privately rated securities were on insurers’ books this year, up from fewer than 2,000 in 2018, the NAIC said. That compares with more than 300,000 separate securities held across all insurers, totaling trillions of dollars.

Starting next year insurers will have to file reports that detail the private ratings received on new investments, which apply particularly to customized financial instruments. Private ratings are supposed to be done the same way as public ones, the NAIC said, so it anticipates receiving reports comparable to what is publicly available on other bonds.

In December, a task force of state regulators at the NAIC said there would be additional, broader scrutiny on all bond ratings after NAIC staff found that firms sometimes have given the same securities widely different ratings. In some cases, private ratings differed by five notches, meaning that one firm considered a bond high quality and safe, while another judged it to be weaker in quality with relatively high risk. Public ratings also sometimes varied, though to a lesser degree. The staff also reviewed 43 privately rated securities and found risk to be materially higher than their ratings indicated.

“We want further discussion on how we currently rely on ratings firms and if we should adjust that framework,” said Carrie Mears, an Iowa regulator who is vice chair of the NAIC’s Valuation of Securities Task Force. More transparency is needed because ratings “have such an impact on the capital position of insurers,” she said in an interview.

A spokesman for S&P Global Ratings said the firm looks forward “to continuing our dialogue with the NAIC in this area.”

“We are confident that the NAIC will find our rating criteria robust and our rating analysis thorough in comparison to the other credit credit-rating firms,” said Kevin Duignan, global analytical head at Fitch Ratings.

The American Council of Life Insurers, a major trade group, said it isn’t aware of any problem with ratings quality. The trade group supports a “study group to answer any questions, and we look forward to working with this group to see if there are any issues,” said Mike Monahan, director of accounting policy.

In the past couple of years, the NAIC has assumed responsibility for sizing up risk in some obscure investment areas. Its small, 35-person Securities Valuation Office, for instance, analyzes principal protected securities, a complex offering that promises protection against loss of principal. Regulators were concerned that raters focused heavily on principal repayment and not the security’s broader performance.

Kevin Fry, an Illinois insurance regulator who chairs the securities-valuation task force, said regulators wouldn’t move too abruptly. “We don’t want to cause markets to freak out,” he said.

Rating Bonds

Read more articles about bonds and insurers, as selected by editors.

Write to Leslie Scism at [email protected]

Copyright ©2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8