For more than a decade, Biogen Inc. BIIB -0.99% worked on a new drug for Alzheimer’s disease that seemed to have blockbuster potential.

Early results were so impressive that Biogen raced toward regulatory approval—a risky gambit that drove up the stock as investors anticipated sales of the first approved drug in nearly two decades to slow the advancement of a disease affecting six million Americans.

Then Biogen changed its mind. The company made an unusual decision to abruptly stop its trials and declare that the drug didn’t work—then reversed course and said the drug did work after all.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the drug in June under a program that fast-tracks promising treatments, despite disagreements within the agency over its efficacy.

The result is a pricey therapy now on the market, Aduhelm, that regulators say isn’t fully proven to work against Alzheimer’s disease. Many patients aren’t taking it because doctors are reluctant to prescribe Aduhelm and Medicare hasn’t decided if it will pay for the drug.

Biogen launched Aduhelm in June at a price of $56,000 a year, only to backtrack in December and cut the price in half to quell backlash over the price. The company’s stock is trading at about half its 2021 high after the FDA approval.

In drug development, management mistakes can be as much of a factor as the complicated scientific questions. With Aduhelm, both played a role.

“All these inconsistencies created one wave of criticism after another—plus Biogen came up with this ridiculous price that added even more fuel to the fire,” said Yaning Wang, who as an FDA official worked on Aduhelm’s approval and is a supporter of the approval. He is now chief executive of a Chinese biotech company.

An FDA spokeswoman said the agency conducted a thorough review of Aduhelm’s data and concluded it warranted approval for patient use “while holding the company accountable for conducting an additional study” to confirm that the drug works. If the study fails, the FDA can pull Aduhelm from the market.

A Biogen spokeswoman said the company realized with hindsight that it made mistakes in stopping the trials early but that it did what it thought was right for patients at the time. Biogen CEO Michel Vounatsos in July told analysts: “Aduhelm was approved appropriately on very solid grounds and represented the right thing to do for patients.”

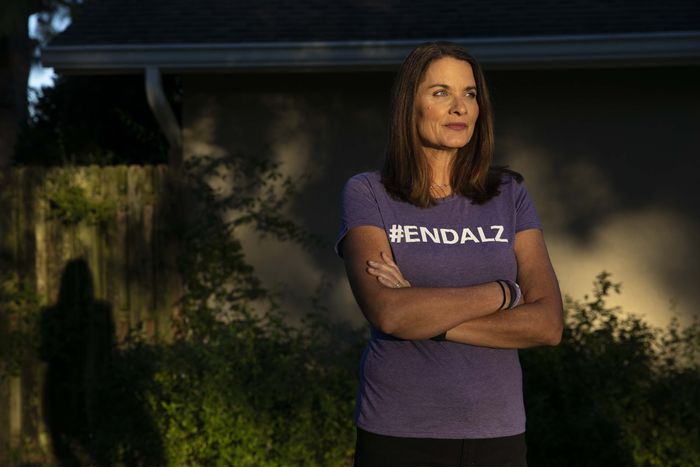

Some doctors say that they have encountered hesitancy among some patients to take the drug but that others are willing to try it. Aduhelm is “a risk that I would take,” said Michele Hall, a 54-year-old former lawyer who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2020 and started Aduhelm treatment in late December. She is willing to try the drug, hoping it will help slow her decline, even if only slightly, she said. “I’ll do whatever it takes to give myself more time.”

Other drugs help alleviate only some of the symptoms of Alzheimer’s. Researchers hope to show Aduhelm can slow the progressive brain deterioration that comes with Alzheimer’s, though it will be years before it can be definitively tested in a new clinical trial.

“Is Aduhelm great? No,” said Marwan Sabbagh, a neurologist at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix and a consultant for Biogen and other drugmakers. “It’s better than the status quo.”

‘I’ll do whatever it takes to give myself more time,’ says Michele Hall, who began Aduhelm treatment last month.

Photo: Eve Edelheit for The Wall Street Journal

Medicare, which covers the majority of Alzheimer’s patients expected to take Aduhelm, is scheduled to make a preliminary decision in January as to whether it will routinely pay for the drug and others like it, and to issue a final coverage decision in April. Medicaid, the joint state-federal health insurance program for the poor, is required to cover Aduhelm, but states are allowed to create special eligibility criteria for which patients are allowed to receive it.

The Department of Veterans Affairs and some private insurers, including Cigna Corp. , have said they won’t routinely cover Aduhelm. A VA spokeswoman said that the agency won’t make Aduhelm available for general use, but that it would consider requests to use the drug on a case-by-case basis. A Cigna spokeswoman said that based on the recommendation of its independent advisers “and well-documented concerns regarding its safety and efficacy, Aduhelm is considered unproven under Cigna health plans.”

High hopes

Aduhelm is a monoclonal antibody, a drug made from living cells that binds to a sticky protein called amyloid, which some scientists think is a cause of Alzheimer’s. The drug attracts other cells to come in and clear the amyloid from the brain. It is modeled on antibodies discovered by researchers at Swiss biotech firm Neurimmune AG in blood samples taken from older people who hadn’t developed Alzheimer’s or who had very slow cognitive decline. It is infused intravenously.

Biogen licensed the rights to Aduhelm in 2007 and had high hopes despite failures of many rivals in tackling Alzheimer’s. For Biogen executives and investors, Aduhelm was key to growth: The company’s sales had been concentrated in multiple sclerosis drugs, where competition was intensifying. Encouraging results from a small early-stage trial on March 20, 2015, sent Biogen’s shares up 10% that day to a price that still stands as its closing record.

Faith that Aduhelm worked against Alzheimer’s became a “religion” among Biogen executives, said Geoffrey Porges, an analyst with investment bank SVB Leerink.

The early results left Biogen officials so confident in the drug’s success that they skipped doing midstage trials, called Phase 2 trials, and proceeded directly in August and September 2015 to launching two Phase 3 trials—large clinical trials testing a drug’s safety and effectiveness that are typically needed to win FDA approval.

Then, a hitch: When Biogen analyzed trial data reflecting patients’ cognitive conditions in early 2019, it indicated the drug wasn’t likely to be proven effective.

By evaluating data midstream in approval-seeking trials, companies can try to predict whether a drug will succeed if the trial continues. Stopping trials early for “futility,” in industry parlance, can save millions of dollars and prevent patients from investing hope on an ineffective drug. Some researchers say the practice can leave crucial questions unanswered about classes of drugs and basic biology.

In a March 2019 meeting, Biogen executives on a small “senior decision team,” as the company called it, concluded that the trials were doomed. Biogen pulled the plug and asked researchers around the world to shut down trials. It told more than 3,000 Alzheimer’s patients who had volunteered that they would no longer receive treatment. Biogen stock fell by nearly 30% the day of the announcement.

A Biogen researcher works on Aduhelm development in 2019.

Photo: David A. White/Biogen/Associated Press

Biogen executives made errors in shutting down the trials. The trial plan called for analyzing data after half of patients completed the study treatment in late December 2018. By the time Biogen completed the analysis in March 2019, three more months of additional data were available—but the decision team didn’t scrutinize the additional data before the company halted the trials, Biogen has said.

A Biogen consultant in the summer of 2018 recommended to senior Biogen statisticians that they consider all available trial data, according to a person involved in the process. The consultant cautioned them that a plan to leave out consideration of additional trial data after the cutoff date—and to leave out certain data from patients in the trial before the cutoff—would open up Biogen to criticism and scrutiny, the person said. The statisticians didn’t heed the consultant’s advice, and it isn’t clear whether the decision team or management considered the recommendation, the person said.

Biogen declined to comment on past discussions with its consultants but said it followed its pre-established statistical-analysis plan.

The decision not to consider the three months of additional data was a misstep, said some clinical-trial experts and statisticians. “Additional data after a study stops is called ‘overrunning.’ We plan for it,” said Scott Emerson, a professor emeritus of biostatistics at the University of Washington who served on an FDA advisory committee that recommended against approving Aduhelm in November 2020. “In this case, the overrunning data was large.”

The Biogen spokeswoman said: “Our decision to stop the trials, though clearly incorrect in hindsight, was based on putting patients at the forefront—as it always should be. Cost was not considered in determining futility.”

Only in the weeks after the trials stopped did Biogen scientists complete a preliminary analysis of the overrunning data and recognize their mistake, the Biogen spokeswoman said. The data seemed to show that one of the trials would have produced positive results, despite the likelihood of a negative outcome in the second trial. Initially, Biogen had analyzed combined data from both trials.

In mid-April, Biogen launched an effort to resurrect the drug with the FDA.

Ms. Hall getting her first Aduhelm infusion last week.

Photo: Doug Hall

Companies rarely pursue approval based on trials halted for futility. Typically, a company abandons the drug or, occasionally, tests it in different patients or diseases.

Biogen officials braced for FDA questions about why it didn’t look at overrunning data before ending the trials and why it was now focusing on just the one positive trial, the person involved in the process said.

Company executives met with FDA officials, including Director of the Office of Neuroscience Billy Dunn, on June 14, 2019, FDA minutes show. FDA officials at the meeting created a working group of Biogen and FDA employees to sort through the clinical-trial data to determine whether it could be used to support a possible submission by Biogen for approval. The joint group was unusual: The FDA typically maintains an arm’s-length relationship with drugmakers.

The FDA spokeswoman said the agency “often works closely with industry to help foster drug development…especially in areas where there is a significant need for treatments for devastating diseases.” A Biogen executive said the working group with the FDA was created because the Aduhelm data needed to be systematically analyzed, requiring frequent meetings to understand the conflicting data results.

Biogen executives saw Dr. Dunn as an ally who had been supportive of Biogen’s early development of Aduhelm and other potential Alzheimer’s drugs, said a person familiar with the company.

Biogen and FDA officials—including Dr. Dunn, agency clinicians and Tristan Massie, an FDA statistician who spearheaded the FDA statistical review—began meeting regularly after the June meeting, according to FDA meeting minutes.

In a summer 2019 meeting, the working group discussed whether Biogen could draw firm conclusions about Aduhelm’s effectiveness because of the difficulty in interpreting incomplete trial data from a prematurely halted trial, according to the person involved in the process.

Aduhelm is designed to slow cognitive decline caused by Alzheimer’s by removing a sticky protein called amyloid from the brain.

Photo: david a white/biogen/Shutterstock

‘Unscientific’

Mr. Massie, the FDA statistician, contested Biogen scientists’ analysis, arguing that there were inconsistencies in the data that made the positive trial’s results unreliable. He also challenged the company’s contention that the failed trial was a statistical fluke, said the person involved in the process, and he argued that the data couldn’t be interpreted after the trials had been stopped for futility.

In one meeting, Dr. Dunn cut him off, saying he was straying from the “core issue” of understanding the data, said the person.

Dr. Dunn and Mr. Massie didn’t respond to requests for comment, and the FDA declined to make them available for interviews.

Mr. Massie’s disagreement with Biogen’s analysis remained outstanding in the months that followed, and he stopped attending working group meetings with Biogen halfway through the process. Meeting minutes the FDA later published suggest the questions Mr. Massie had raised about the Biogen analysis had been addressed by February 2020 according to FDA documents.

Mr. Massie’s objections became public when an FDA outside advisory committee convened a hearing on Nov. 6, 2020, to advise on whether to approve Aduhelm. In a recorded presentation at the hearing, Mr. Massie called Biogen’s data analysis “unscientific, statistically inappropriate and misleading,” and recommended against approval.

His FDA colleague Dr. Dunn, in contrast, pointed to what he said were “robust” and “exceptionally persuasive” trial data supporting Aduhelm’s approval. The outside advisers sided with Mr. Massie in the hearing, unanimously rejecting the drug’s approval.

On June 7, the FDA approved Aduhelm and Biogen’s stock closed up 38% from the day before.

Photo: Associated Press

Dr. Wang, then director of the FDA’s Division of Pharmacometrics, said he dug into the data and questions raised by the advisory committee that weren’t answered. These included why the FDA hadn’t considered Biogen’s failed trial as a verdict on the drug’s effectiveness.

Dr. Wang, who left the FDA in September, said he found Mr. Massie’s analysis contained data-entry errors and methodological misjudgments, resulting in what he said were flawed conclusions in Mr. Massie’s recorded presentation at the hearing.

He said Mr. Massie’s analysis didn’t emphasize average changes in patients across Biogen’s trials showing that a slowing in subjects’ cognitive decline correlated with lower levels in their brains of amyloid.

Dr. Wang said he told Mr. Massie that he had found what he believed were errors in Mr. Massie’s analysis and offered to jointly prepare a new statistical analysis but that he never heard back. In spring 2021, a council of senior FDA officials was asked for its advice on approval, he said. Dr. Wang said he and others made presentations.

Nearly every FDA council member voted against approval on April 7, 2021, just as the outside advisers had.

Fast-track approval

On April 26, seven FDA leaders—some were on the earlier council—met to consider Aduhelm for accelerated approval, a fast-track program that lets the FDA clear drugs for serious diseases before their medical benefits are fully proven. Five of the FDA officials supported approving the drug on the condition that Biogen do another trial, FDA documents show. The head of Mr. Massie’s biostatistics office voted against approval of any kind, while a seventh official abstained.

On June 7, 2021, the FDA approved Aduhelm. Biogen’s stock closed at $395.85 that day, up 38% from the previous closing price, and reached a 52-week closing high of $414.71 on June 10.

Harvard Professor of Medicine Aaron Kesselheim, who was on the outside-adviser committee and resigned from it to protest the approval, in his resignation letter called it “probably the worst drug approval decision in recent U.S. history.” Dr. Kesselheim in an email said he objected to the approval because Aduhelm “has no clear evidence of efficacy plus the very real risk of potentially serious harms” and because the FDA’s “process was problematic due to the last-minute switch to accelerated approval.”

The FDA said in a written statement that “given the unmet needs for patients with Alzheimer’s disease—a serious, progressive, and ultimately fatal disease—the Agency chose to use the accelerated approval pathway to allow earlier access to patients.” Biogen and the FDA say Aduhelm’s most serious potential side effect—swelling or small bleeds in the brain—typically doesn’t cause symptoms in patients and can be safely managed by regularly monitoring patients with MRI scans.

As of October, Biogen said, only about 120 U.S. medical facilities had administered Aduhelm to patients out of the more than 900 sites that the company says were prepared to administer the drug when it was approved in June, leading to $300,000 in revenue in the third quarter, far short of the $12 million analysts projected.

Some hospitals have said they won’t administer Aduhelm to patients because of uncertainty over the drug’s effectiveness and concerns about its potential side effects.

Raymond James Financial Inc. analyst Steven Seedhouse called Aduhelm “potentially the worst drug launch of all time” in terms of sales in an Oct. 20 research note to clients.

The Biogen spokeswoman said: “We continue to see a high level of patient interest and we are making steady progress in the launch of Aduhelm.” In October, Chief Financial Officer Michael McDonnell told analysts that “over the long term we continue to believe that it’s a very meaningful multibillion-dollar opportunity.”

Biogen’s $56,000 launch price, announced June 7, was as much as 19 times as great as what would be considered a fair price, according to an analysis published in August by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a nonprofit research and advisory group that does cost-effectiveness analyses that insurers and drug companies use.

Biogen said the analysis underestimated the severity of Alzheimer’s and the value of treatments to patients.

‘Aduhelm was approved appropriately on very solid grounds,’ Biogen’s CEO said in July; Biogen headquarters in Cambridge, Mass.

Photo: Erin Clark/The Boston Globe/Getty Images

The Alzheimer’s Association, a nonprofit advocacy group that had campaigned for approval, in a June 12 press release called the price “simply unacceptable.”

In December, Biogen said it was lowering Aduhelm’s price after listening “to the feedback of our stakeholders” over the past several months. On Dec. 20, the Alzheimer’s Association said that Biogen’s price cut was an important first step in ensuring access to the drug, but that more needed to be done, including for Biogen to provide financial support to patients for whom cost was still a barrier to treatment.

Criticism of Aduhelm’s price and doubts over its effectiveness drove down Biogen shares in the months after approval. Through Jan. 4, the stock had fallen 42% from its 2021 closing high on June 10.

Aduhelm’s launch price made doctors and hospitals even more reluctant to prescribe Aduhelm, said Ronald C. Petersen, a Biogen consultant and director of the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. Dr. Petersen said the price cut could make Aduhelm more affordable for some patients, but that wouldn’t alone create a groundswell of demand. The coming decision by Medicare on whether it will cover the drug will likely be the most important factor for whether more doctors and patients embrace it, he said.

“If there’s no real documented clinical benefit yet,” said Dr. Petersen, “is it really worth that?”

Write to Joseph Walker at [email protected] and Susan Pulliam at [email protected]

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8