Viking

We might obtain an affiliate fee from something you purchase from this text.

New York Instances monetary columnist Andrew Ross Sorkin’s “1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History – and How It Shattered a Nation” (Viking) appears again to the nation’s most catastrophic market collapse.

Learn an excerpt beneath.

“1929” by Andrew Ross Sorkin

Want to hear? Audible has a 30-day free trial accessible proper now.

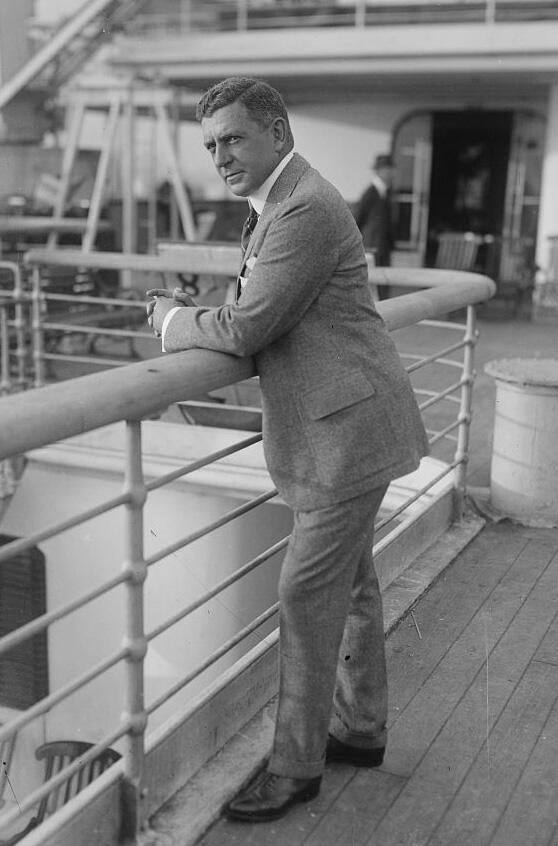

Charles Mitchell strode up the steps of 55 Wall Avenue, decided to undertaking his normal sense of confidence and certitude. It had been a crushing afternoon. As he returned to his workplace, he knew that the eyes of Wall Avenue have been on him — everybody from the merchants on the street to his personal secretary was assessing his gait and looking his face, attempting to learn which means into each twitch, each line, each wrinkle.

In his grey three‑piece swimsuit, shoulders again, Mitchell saved up his smile as he handed by the glass‑domed central corridor of his Nationwide Metropolis Financial institution. With its eighty‑three‑foot ceiling and two strong bronze doorways defending a secure weighing some 300 tons, the financial institution was the biggest within the nation.

Banker Charles Mitchell, c. 1925-29.

Library of Congress

It was simply previous 5:30 p.m. on Monday, October 28, 1929. Hours earlier, the inventory market had closed with a pointy, dizzying drop of 13 p.c after every week of downward convulsions; at this time was by far the best fall. The darkening downtown streets nonetheless teemed with anxious brokers of their fedoras and flat caps, messenger boys and switchboard ladies, all gossiping and speculating in regards to the collapse. What brought about the autumn? How a lot additional would possibly it go tomorrow? Would the markets even open?

As Mitchell made his strategy to his workplace, the teller home windows he handed mirrored the weary puffiness below his eyes and his raveled, graying eyebrows. He collapsed into the chair behind his mahogany desk. The room was furnished with the excessive formality befitting an eighteenth‑century statesman: vintage wooden chairs, a grandfather clock that stood towards the cream‑white woodwork flanked by portraits of George Washington orchestrating the newly unbiased nation with the aim and resolve that Mitchell sought to emulate in his personal life.

The athletic fifty‑two‑yr‑previous financial institution chairman — an unusually optimistic man whom the press referred to as “Sunshine Charlie” — had spent the afternoon in emergency conferences on the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York, puzzling over the right way to calm the market. It was a second for which a self‑consciously Nice Man like Mitchell ought to have been totally ready. He had the expertise, the stature, and the steely nerves essential to steer Wall Avenue by these robust occasions.

But he felt uncovered, weak.

However he didn’t have time to contemplate his emotional state.

He walked upstairs to discuss with Hugh Baker, who ran Nationwide Metropolis’s inventory‑buying and selling unit.

Baker, a tall, bald man with piercing eyes, started to elucidate to Mitchell, calmly, if considerably obliquely, what had taken place whereas Mitchell had been on the Federal Reserve.

“Our portfolio today has been tremendously increased in our holdings of National City Bank stock,” Baker instructed him.

Mitchell stared at him, ready to listen to precisely what he meant.

Baker lastly blurted out: “We purchased seventy‑odd thousand shares.”

Mitchell, who might calculate numbers immediately in his head, instantly grasped the character and scale of the issue. That’s unbelievable, he thought. The financial institution didn’t have the money to pay for thus many shares. He was outraged — and terrified. Every little thing he had constructed was abruptly at grave danger of collapse.

Barely a month earlier, Mitchell had been on high of the world. He had finalized an settlement to take over the Corn Trade Financial institution, a daring acquisition that will flip Nationwide Metropolis from the biggest financial institution within the nation into the biggest on the planet, stealing the mantle from London and serving to New York lastly eclipse its rival metropolis because the world monetary middle. This was historical past within the making, an overthrow of the established order, the sort of gambit that made Mitchell a king amongst males.

However to tug off the deal, Mitchell had made a giant — and dangerous — guess on the energy of his personal inventory. Corn Trade shareholders might take $360 in money for every of their shares, or 4 fifths of a share in Nationwide Metropolis Financial institution. On paper, the inventory was the higher deal: So long as Nationwide Metropolis inventory stayed above $450, 4 fifths of a share was value greater than $360 in money. On the time the deal was struck, it was comfortably larger, buying and selling at $496 a share. Mitchell wanted it to remain there till the deal could possibly be accomplished, seemingly within the subsequent month — as a result of, in fact, Nationwide Metropolis didn’t have the money to pay everybody, a vital element he saved to himself.

So he quietly instructed his merchants to purchase the financial institution’s shares at any time when the value slipped.

In a comparatively steady market, this posed no drawback. Huge publicly traded firms purchased again their very own shares on a regular basis. In a quickly falling market, nevertheless, doing so might rapidly turn into like shoveling cash right into a furnace, which was what had been taking place that afternoon. Within the chaos of all that promoting stress, Nationwide Metropolis’s bids had been accepted so rapidly that they misplaced monitor of what number of that they had amassed. By the point merchants received a deal with on the scenario, Nationwide Metropolis had dedicated to purchase seventy‑one thousand of its personal shares, excess of it might afford to carry.

There have been only a few good choices. To fund their every day operations, huge banks like Nationwide Metropolis needed to continuously borrow towards their property. However banking regulation prevented them from providing their very own inventory as collateral. Thus, these seventy‑one thousand shares — which price about $32 million — have been a deadweight that might probably take down the entire financial institution.

“It would be embarrassing for us to attempt to borrow on that stock in other banks,” Mitchell stated, realizing full nicely that his rivals would seize on any such transfer as an indication of vulnerability. With the market in free fall, brief sellers — merchants who guess that shares would go down — have been lining up targets, probing for weak spot.

The inventory market was on the breaking level. Gross sales quantity had overwhelmed the human equipment of the buying and selling flooring to such an extent that, on the earlier Thursday, the ticker had fallen 4 hours behind in reporting inventory costs, greater than twice the longest earlier delay.

What this meant was that the large board of costs that loomed over the ground of the New York Inventory Trade was hopelessly inaccurate. Buying and selling shares on this setting was like being a gambler at a baseball recreation within the eighth inning and taking a look at a scoreboard that hadn’t been up to date for the reason that third, whereas all people round you was shouting conflicting opinions about which workforce was forward and by how a lot. The costs of shares bought privately — referred to as “off‑exchange,” which was the case with Nationwide Metropolis shares — have been even additional behind as a result of they have been tied to the broader market’s actions with out being absolutely up to date in actual time, exacerbating the delay. For Wall Avenue merchants, the one prudent resolution was to promote and get the hell out of the market. Which is strictly what they have been doing.

Mitchell knew that if he tried to unload even a small fraction of Nationwide Metropolis’s place again into such a weak market, rumors would start to fly in regards to the financial institution’s solvency, and that might simply flip right into a vicious cycle that will be unimaginable to cease. If costs declined quick sufficient, it might set off a a lot bigger disaster: A “lack of confidence might bring a run,” Mitchell instructed Baker, envisioning depositors lining up exterior each one among its fifty‑eight branches across the nation.

A run on the nation’s largest financial institution. There was nothing bankers feared extra.

Get the guide right here:

“1929” by Andrew Ross Sorkin

Purchase regionally from Bookshop.org

For more information: