The nation’s aging power grid is under pressure. Instead of adding to the strain, could millions of electric vehicles help rescue it?

Technology firms, utilities and manufacturers are testing the ways that the electric grid can function as a two-way street, with electric vehicles—or EVs—acting as a fleet of batteries ready to be tapped when parked. The idea that the batteries of electric vehicles could help supply a region’s power grid during emergencies or peak-demand periods has a name: vehicle-to-grid, or V2G. And then there is V2X—that is, vehicle-to-anything.

“Imagine that after a hurricane or wildfire causes widespread power outages, electric school buses are used to power storm shelters,” says Stan Cross, electric transportation policy director at the nonprofit Southern Alliance for Clean Energy. “Electric work trucks provide power to first responders, electrified municipal fleets keep hospitals operating, and the EV in your driveway keeps your lights on, your fridge cold, your phone charged.”

Vehicle-to-grid ideas have gained attention as the U.S. electrical system, stressed by aging equipment and weather disruptions, has become less dependable. Utilities also see electric-vehicle batteries as a potential new reliable resource at a time when the U.S. is rapidly adding wind and solar farms, which avoid greenhouse gas emissions but provide intermittent power. Vehicle-to-grid will be one way to help meet sustainability goals and move toward more renewables, says Jim Poch, electric transportation manager at Duke Energy Corp. , which has pilot projects to test electric school buses as power sources in North Carolina and Indiana. “The grid is going to have to get more intelligent and distributed.”

While vehicle-to-grid and V2X technologies exist, few people are using them—or driving EVs, for that matter. Market share of all-electric vehicles in North America is around 3.3% according to industry data tracker EV-volumes, lagging that in Europe and China. But sales of EVs in the U.S. are growing at a faster pace than those of gasoline-powered vehicles. Startups focused on vehicle-to-grid power raised $400 million in venture capital last year, up from $232 million in 2020, according to research firm PitchBook.

Vehicle-to-grid power could help delay or avoid eventual system upgrades, such as replacing or adding power lines, as use of EVs and other electrical items rises, says John Isberg, a vice president at utility National Grid.

But the vehicle-to-grid concept faces hurdles. Sending power from a vehicle to utilities or to a home requires special technology and chargers. Some pilot tests show that using a vehicle as a power source can wear on batteries, causing them to degrade more quickly. And using electric cars and trucks as emergency home generators could be easier for owners to embrace than a role providing power for the grid. Creating market incentives for individual EV owners will be crucial, those working on vehicle-to-grid efforts say.

“I think we’re really, really close,” says Annette Clayton, chief executive of North America for Schneider Electric SE, a manufacturer of electrical products and provider of technology and services. But finding a viable commercial model is a roadblock, she says. “Who contributes, who gets compensated, what motivates individuals to want to bring their vehicle to the grid? I think it’s more of a digital challenge than a hardware challenge.”

Electric school buses—which sit idle at predictable times that often coincide with summer heat waves and other periods of peak power demand—have been among the first candidates for trying vehicle-to-grid. Programs across the U.S. run by utilities, tech firms, manufacturers and the owners or operators of fleets are testing how this system works best for utilities and the grid, how much it can cut electricity costs for owners, and how much it harms battery life.

A school bus in Beverly, Mass., provided power to the utility National Grid in the summer of 2020.

Photo: Highland Electric Fleets

“V2G functionality definitely helps the grid in the summer,” says Raghusimha Sudhakara, director of e-mobility and demonstrations at Consolidated Edison Inc., which tested the technology with electric school buses in White Plains, N.Y. from 2018 to 2021. “There’s no question about that.”

Results were mixed on whether the higher cost of bidirectional charging hardware compared to standard equipment or the additional battery degradation was worth it for the owners and operators of the buses, Mr. Sudhakara says. “We did find that the battery capacity degrades. The battery doesn’t instantly fail. It kind of fades in its capacity.” The exact impact of V2G and V2X on battery life is unclear and a subject of debate and research in pilot projects across the U.S.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

Are you driving or considering buying an electric vehicle? What do you see as the advantages and disadvantages? Join the conversation below.

Drivers will have to balance potential benefits from offering their vehicle as a power source—say, payments for supplying power to the grid—against the wear on batteries, says Quincy Lee, chief executive and founder of Electric Era Technologies Inc., which makes battery-storage systems for EV fast-charging stations. While home emergency power provides a clear benefit to the owner, services that help a utility or the grid could be a harder sell, he says. “I think the big question for the industry is, what programs are the most lucrative [for drivers] and what is the penalty for drivers?”

A vehicle-to-grid program that wears out a battery well ahead of the expected life span could anger owners if they aren’t paid enough to cover the costs, for instance. “There is margin to be squeezed out of the average driver’s daily habits and also the car’s lifetime capabilities,” Mr. Lee says. “I don’t think it’s going to be full, ubiquitous adoption and the massive bank of extra energy storage that people think that it’s going to be because, basically, the first thing people buy a car for is transportation. If you degrade the life of the asset, what are you doing?”

Ms. Clayton of Schneider Electric thinks concerns about battery degradation are overstated. Having batteries sit fully charged for long periods also causes wear, she notes. But, she adds, “the pilots will help everybody learn a lot.”

Automakers will have a major say in whether vehicle-to-grid can go forward because vehicles need to be enabled for two-way electricity flow. Selling electricity to the grid will also require certain software and chargers. So far carmakers are mixed on offering the option to drivers. Ford Motor Co. this spring plans to launch the F-150 Lightning, an electric version of its franchise pickup truck, touting it as a source of emergency-backup power. But Tesla Inc., which dominates the electric-car market, doesn’t support the ability to feed power to a home or into the grid.

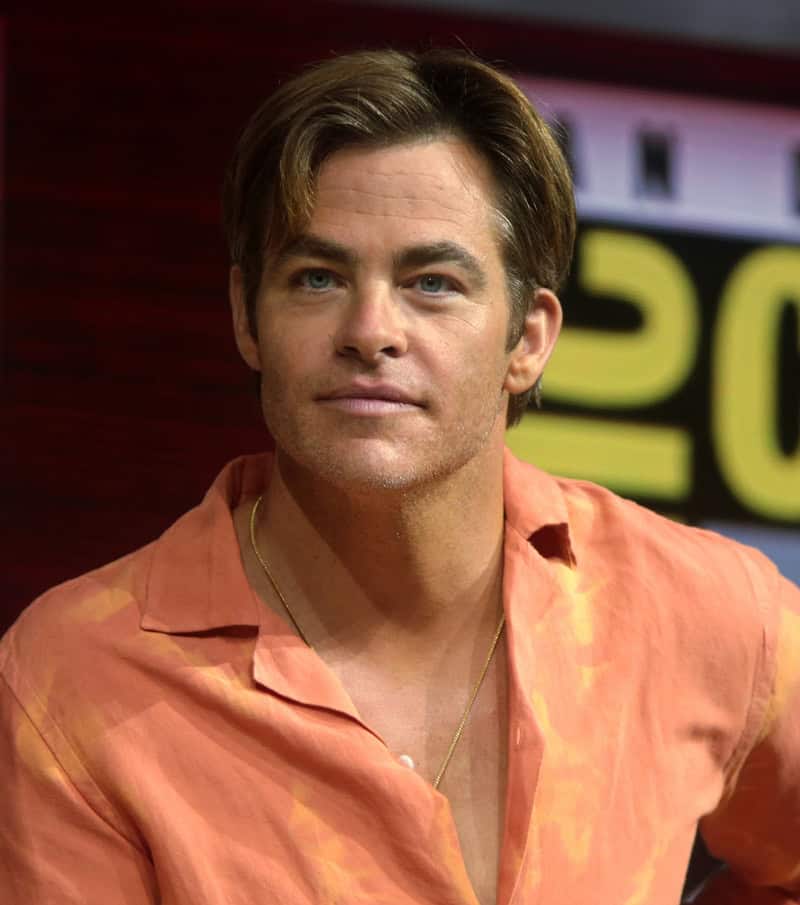

Ford Motor Co. in May unveiled its electric F-150 Lightning pickup truck, touting it as a source of emergency-backup power.

Photo: JEFF KOWALSKY/AFP/Getty Images

“Automakers have to get comfortable with bidirectional chargers because ultimately the automakers are standing behind the warranties for their vehicles,” says Pooja Goyal, chief investment officer of the infrastructure group at Carlyle Group Inc. private-equity firm.

EV drivers can now charge with charging stations, costing around $500, that deliver power into vehicles. Vehicle-to-home or vehicle-to-grid would require a charger that allows energy to flow two ways. Several models likely to cost in the range of $5,000 to $6,000 are expected to come to market this year in the U.S., says David Slutzky, founder and chief executive of Fermata Energy, a supplier of V2X technology.

Vehicle-to-home could replace backup generators for some homeowners, while vehicle-to-grid programs could lower ownership costs of EVs, which are more expensive than gas-powered vehicles, Mr. Slutzky says. “The massive storage we absolutely have to have available to the grid to enable scaled renewables is going to be under the hood of cars,” he says. “And the ability to access that is going to favorably impact the actual cost of a vehicle because they can now earn money.”

Write to Jennifer Hiller at [email protected]

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8