This is the first in a six-part series on “two years and counting” for the coronavirus.

Congress has approved about $6 trillion for the fight against COVID-19, or more than it spent to defeat Nazi Germany and imperial Japan in World War II.

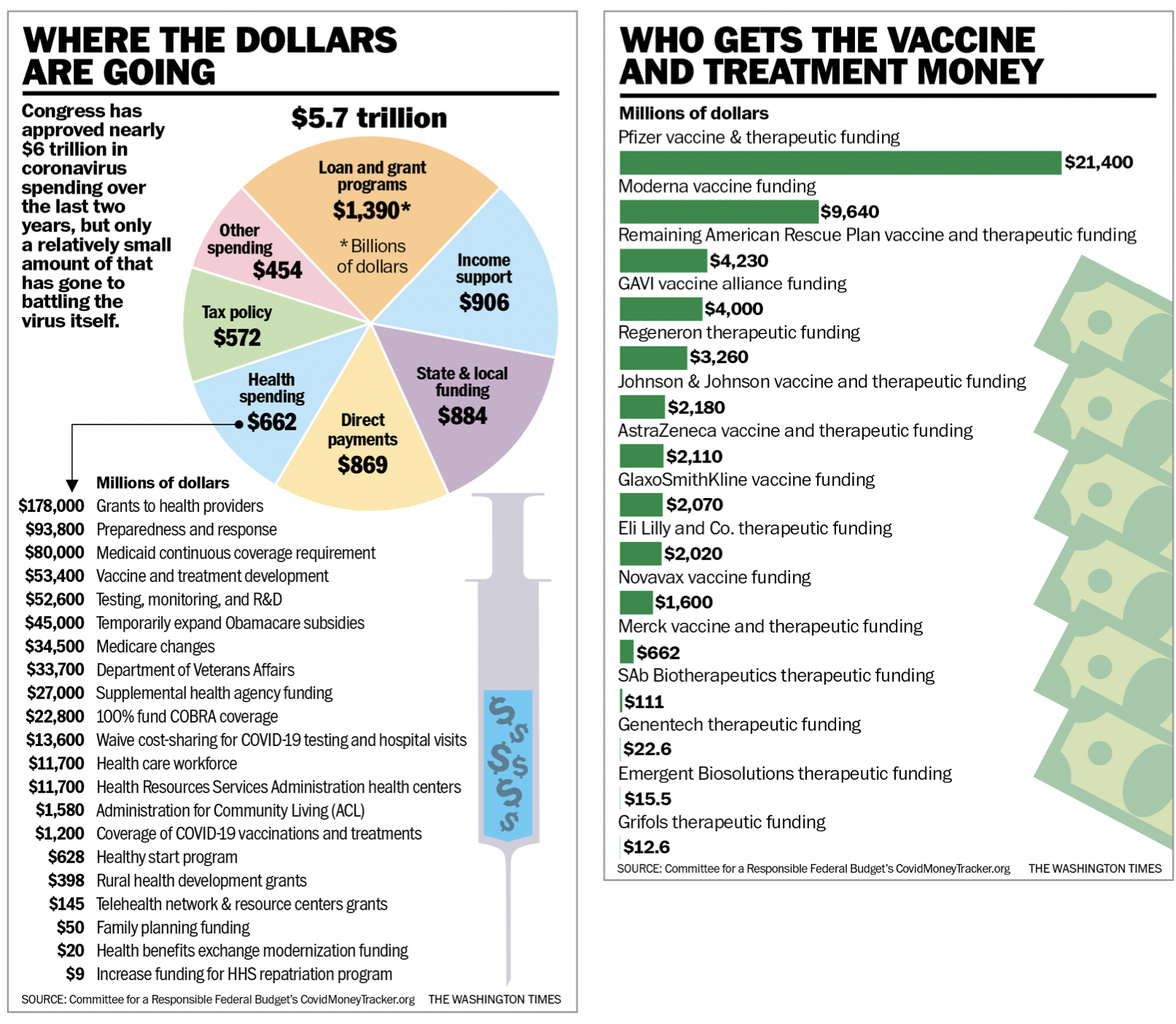

Yet Uncle Sam has spent only a small fraction of that money — 15% or less, depending on who’s counting — on beating the coronavirus itself.

The $50 billion or so aimed at vaccines and therapeutics is less than Congress allocated for an Obamacare expansion, tucked into the same pandemic spending bills. Another $53 billion allocated to coronavirus testing and monitoring is dwarfed by an $81 billion bailout for private pension funds that Democrats stuck inside their massive American Rescue Plan bill last year.

“On overall levels of spending, we missed badly,” said Andrew Lautz, director of federal policy at the National Taxpayers Union. “I don’t want to suggest the federal government should have spent nothing. This was a multitrillion-dollar public health and economic problem that very likely over the course of several years required a multitrillion-dollar response. I think $5 trillion was an overshoot.”

Congress has approved six bills with significant pandemic relief funds. Mr. Lautz figures only about 15% of the money has gone toward public health measures.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget figures it’s less than that — about $300 billion, which works out to about 5% of the money Congress approved.

It turns out that the relief may not have been enough. As the country enters its third year of the pandemic, the White House and congressional Democrats have said they will need to come back to taxpayers for a seventh pandemic spending package.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget runs the COVID Money Tracker website, a one-stop shop for understanding the broad outlines of pandemic spending. It shows that even as money for unemployment benefits, assistance to small businesses and cash for state and local governments sped out the door, the public health spending lagged.

“Some of this is by design,” said Marc Goldwein, the senior vice president and senior policy director at CRFB. “Sometimes it’s spending slow because it’s supposed to spend over a period of time or because people expect it to.”

Whatever the reasons, the spending decisions Congress has made have received less attention than philosophical debates over masking and vaccine mandates. Still, they are no less central to combating COVID-19.

The effects of the spending surge last for decades. In February 2020, just as the novel coronavirus was beginning to spread across the U.S., federal public debt stood at $17.2 trillion. It’s now hovering around $23.4 trillion.

Turning on the money spout

To win World War II, Uncle Sam spent nearly $300 billion in 1940s money, according to the Congressional Research Service. Adjusting for inflation, that works out to about $5 trillion, by far the costliest war in U.S. history.

That bought 47 billion rounds of ammunition, 12 million infantry rifles, 300,000 aircraft, more than 200 submarines and plenty of other war machinery.

COVID-19 tops that.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget says Congress has approved $5.7 trillion, with $4.9 trillion disbursed or committed. The executive branch has made another $900 billion in administrative moves, and the Federal Reserve’s monetary response tops $7 trillion, CRFB says.

CRFB says the spending roughly breaks down to $1.4 trillion in grants and loans to businesses; $906 billion to directly support Americans through unemployment benefits, student loan delays and food assistance; $869 billion for stimulus checks; $662 billion for all health spending, which goes well beyond fighting COVID-19; $572 billion in tax changes; and $884 billion for states and localities.

That last category has proved particularly controversial, given that most states have generated strong revenue during the pandemic.

Other estimates put total COVID-19 relief spending slightly lower than the CRFB’s numbers. The National Taxpayers Union calculates that spending and tax cuts have totaled $5.1 trillion. The Government Accountability Office said Congress has allocated $4.6 trillion, obligated about $4 trillion and spent $3.5 trillion.

Whatever the figure, it’s about to grow once President Biden submits his request for another round of money.

Lawmakers on Capitol Hill are pondering whether to attach it to the catchall spending bill they want to pass by Feb. 18.

The bigger question is whether the money would be added to what has already been allocated or whether Republicans can force Democrats to recapture COVID-19 money Congress has approved but the administration hasn’t spent.

Lawmakers also will have to figure out how much to spend on public health in the U.S., how much to spend on programs around the world and whether to attempt another round of economic stimulus.

Early in the pandemic, that question was easy.

Mr. Lautz said the first bill Congress passed, an $8 billion measure in March 2020, was about 75% for public health. The second bill, a $200 billion measure approved a couple of weeks after that, was about 80% for health.

The next four bills got into far more than health, which never topped 20% of the total spending, Mr. Lautz said.

“Congress really shifted from a primary public health focus on their COVID relief legislation to an economic relief focus,” he said.

The self-described budget wonk said he doesn’t know whether enough money went to health spending, but 15% seems the wrong balance.

It’s worth asking whether the U.S. got its money’s worth from the spending.

As of October, according to the International Monetary Fund, the world had spent a total of $10.8 trillion to grapple with the pandemic, with about $1.5 trillion going to health measures. The U.S. accounts for about half of that spending.

Measured another way, the U.S. has spent about 25% of gross domestic product on the pandemic and currently has a death rate of about 2,700 per 1 million people. South Korea has spent 6.4% of its GDP, and its death rate is 134 people per 1 million — 20 times better.

Poland, whose death rate is similar to that of the U.S., spent 6.5% of GDP on COVID-19 measures.

Vaccine makers rake in cash

Health experts now say the virus is here to stay and suggest annual vaccine boosters may be needed.

That is fueling questions about whether pandemic spending is a permanent part of the federal budget.

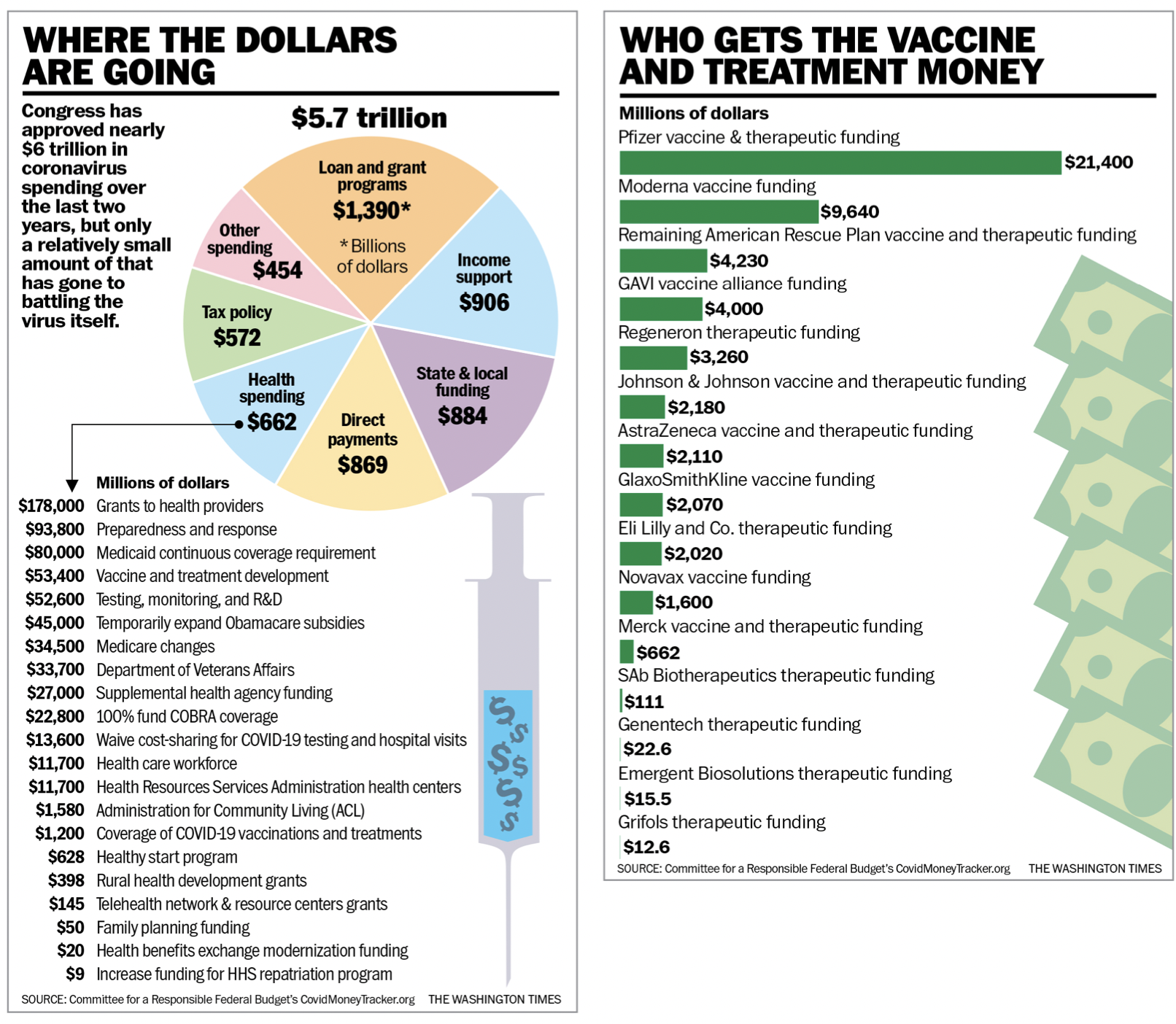

With more than 9 billion doses of vaccines administered globally, and more than 500 million in the U.S. alone, the manufacturers have had a windfall and believe demand is just beginning.

“Today, we are reasonably certain that SARS-CoV-2 is here to stay,” Kathrin Jansen, Pfizer’s head of vaccine research and development, said in a December call with investors.

Pfizer, which developed its vaccine, Comirnaty, in an alliance with German firm BioNTech, shipped 2.4 billion doses to more than 160 countries in 2021 and posted $36.8 billion in revenue from the vaccine last year.

Governments around the globe had secured contracts for 1.9 billion more doses in 2022 as of the end of last year, for another $32 billion in revenue, and Pfizer expects the year’s total to reach 4 billion doses.

Johnson & Johnson, with about 3.5% market share in the U.S., is projecting $2.4 billion in sales in 2021.

Other U.S. manufacturers stand to post significant profits from the vaccine in 2021 as well.

Moderna, which produces the second-leading shot in the U.S., said it shipped 807 million doses worldwide in 2021 and raked in an expected $17.5 billion in revenue.

The company has signed about $18.5 billion in advanced purchase agreements for 2022, with an additional $3.5 billion in options, according to figures presented at the J.P. Morgan Health Care Conference in January.

It’s not just the drug manufacturers getting federal cash.

The Biden administration in recent weeks announced the purchase of 500 million rapid tests to be doled out to Americans for use at home, at a cost of $4 billion.

The White House is pulling 400 million N95-style masks from the national stockpile. At nearly $6 a mask — the rate the government is paying during the pandemic — the price tag is more than $2 billion.

Competition coming

If Pfizer’s projections are correct, demand for annual revaccination shots would outpace annual flu vaccines, valued at more than $5 billion globally in 2020, well beyond 2024. That’s when COVID-19 is expected to become endemic.

Pfizer says it is well-postured for a more competitive market, especially one that will be forced to respond to evolving variants, given its messenger-RNA platform used for its COVID-19 vaccine. Moderna’s vaccine is also an mRNA-type vaccine.

The technology, which has been studied for decades but became available to the public only with the fielding of COVID-19 vaccines, allows companies to update their vaccines quicker to respond to new strains of the virus. Pfizer has said it can update its vaccine to respond to new strains within 100 days.

James Love, director of Knowledge Ecology International, a Washington-based nongovernmental organization focused on access to medical technology and trade policy, said the technology will not necessarily remain competitive.

“The question is: Can they come up with new variant vaccines as fast as new variants come up?” he said.

He said the technology undoubtedly will be important in the future but has by no means made other technologies obsolete. Legacy vaccine technologies are still in play for effective responses to the virus, he said.

These tried-and-true technologies, in many cases, are far more accessible for companies that don’t have the deep pockets needed to get the technology off the ground.

“In the booster market right now, you see people working on vaccines right now that are not messenger-RNA,” he said. “These are Big Pharma companies, and so they must think like we do: that messenger-RNA is not the only game in town.

“I think it will be more competitive than people think,” Mr. Love said.

Congress soon might have answers about the vaccine market if lawmakers include funding for future booster shots in the COVID-19 spending package.

Under contracts already in place, the U.S. has the option of buying 1.2 billion doses, according to a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services.

When or where Uncle Sam’s cutoff line is, nobody knows.

“To date, [the government has] made a commitment that they’re going to be buying vaccines for people in the United States,” Mr. Goldwein said. “The question is: When, if ever, does that shift?

“This could be the type of thing that ultimately goes on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and they are paying for COVID vaccines for the next 200 years,” he said. “That’s one possibility. The other possibility is that, at some point, they say the public health emergency is over. But as of now, my assumption is the federal government is intending to cover Americans’ vaccine expenses for the foreseeable future.”

For more information, visit The Washington Times COVID-19 resource page.