For more than a year it seemed as if the stock market could only go up, buoyed by a river of money that gushed from the government. In the past week, that illusion has been shattered.

Growing certainty that the Federal Reserve intends to raise interest rates, most likely as early as March, sent investors scurrying. On Monday, the Dow Jones Industrial Average moved 1,000 points in a single day—twice. It sank more than 3%, then roared back up to close with a gain. Stocks gyrated the rest of the week, with the S&P 500 down more than 9% so far in 2022 and the Nasdaq-100 index off more than 14%.

But what happens next isn’t the right question to ask.

In a speech in 1963, the great investment analyst Benjamin Graham said: “In my nearly 50 years of experience in Wall Street I’ve found that I know less and less about what the stock market is going to do, but I know more and more about what investors ought to do.”

You ought to do two things. First, put the market’s recent fluctuations in long-term perspective. Then, recognize that what kind of an investor you are matters more than which investments you own.

There’s nothing abnormal about the way stocks have been heaving up and down the past few weeks. It’s the calm of last year, when stocks rose almost 28% but fluctuated with about two-thirds their usual intensity, that was abnormal.

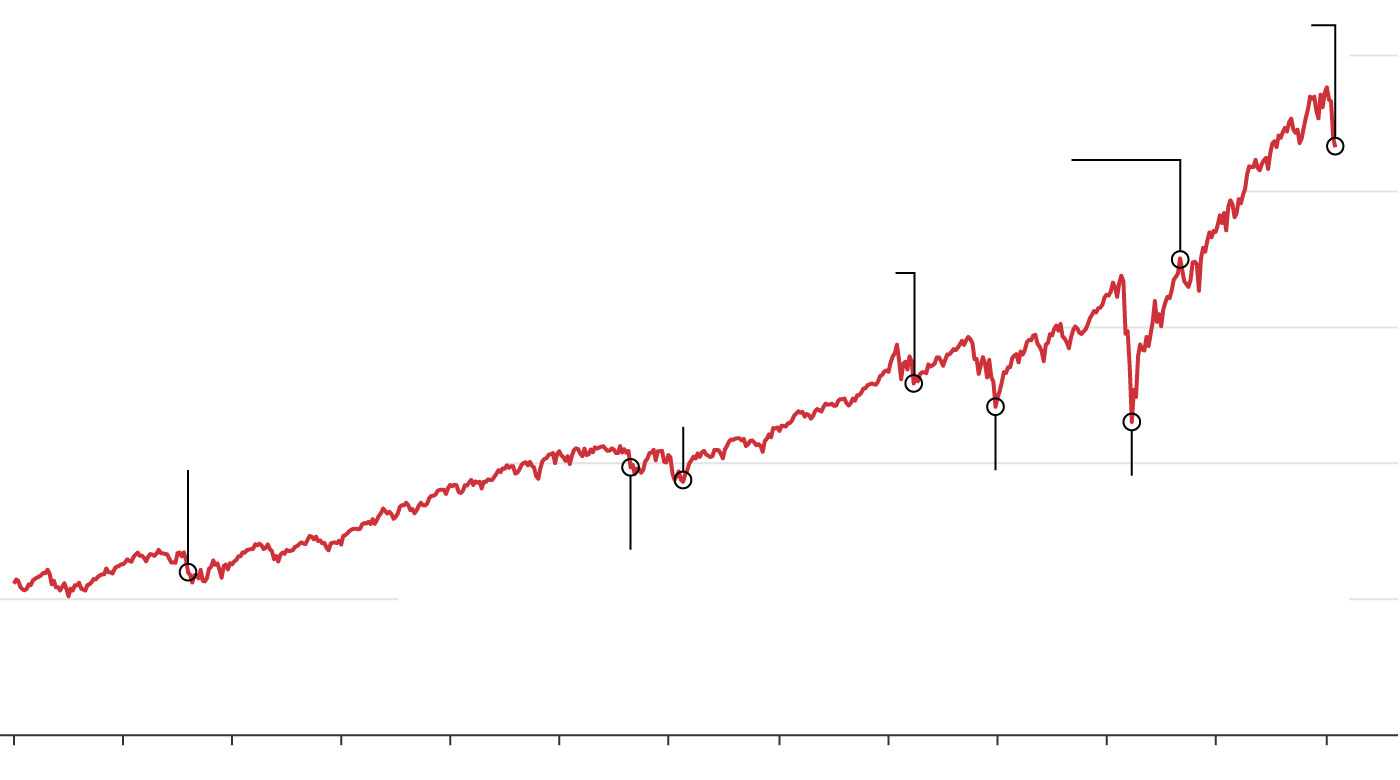

Choppy Waters

January 2022: Stocks fall almost 10% as the Federal Reserve signals its intention to raise interest rates.

The S&P 500’s long rise might have felt steady to some investors until recently, but it has dropped many times along the way.

August 2020: Stocks hit a new all-time high, up 56% from the March low in less than five months.

March 2018: The Trump administration’s talk of trade wars unsettles stocks.

February 2016: Stocks sink roughly 10% from January highs as oil prices plunge.

August 2011:

Standard & Poor’s downgrades U.S. debt from AAA.

December 2018: Stocks suffer their worst December since 1931, falling 9%.

March 2020:

Stocks fall 34% in 23 trading days as Covid-19 puts the global economy into lockdown.

August 2015: Collapsing stock prices in China knock U.S. shares down by almost $2 trillion in a week.

Choppy Waters

The S&P 500’s long rise might have felt steady to some investors until recently, but it has dropped many times along the way.

August 2011: Standard & Poor’s downgrades U.S. debt from AAA.

February 2016: Stocks sink roughly 10% from January highs as oil prices plunge.

December 2018: Stocks suffer their worst December since 1931, falling 9%.

March 2020: Stocks fall 34% in 23 trading days as Covid-19 puts the global economy into lockdown.

August 2020: Stocks hit a new all-time high, up 56% from the March low in less than five months.

January 2022: Stocks fall almost 10% as the Federal Reserve signals its intention to raise interest rates.

Choppy Waters

The S&P 500’s long rise might have felt steady to some investors until recently, but it has dropped many times along the way.

August 2011: Standard & Poor’s downgrades U.S. debt from AAA.

February 2016: Stocks sink roughly 10% from January highs as oil prices plunge.

December 2018: Stocks suffer their worst December since 1931, falling 9%.

March 2020: Stocks fall 34% in 23 trading days as Covid-19 puts the global economy into lockdown.

August 2020: Stocks hit a new all-time high, up 56% from the March low in less than five months.

January 2022: Stocks fall almost 10% as the Federal Reserve signals its intention to raise interest rates.

Two factors had kept stocks rising smoothly until this month: government policy and investment automation.

The Federal Reserve’s low-interest-rate stance, and trillions of dollars of stimulus spending, inundated the markets with cheap money. That drove stocks up.

And, whenever declines get steep, financial advisers and retirement funds send in automatic buy orders that mechanically purchase stocks as they fall below a target level. That has kept stocks from falling too far.

Such smoothness can breed complacency.

“We go through these long regimes of normal to low volatility,” says Joanne Hill, head of research and strategy at CBOE Vest Financial, an investment-advisory firm in McLean, Va. “And then you have these spurts of market storms that come through.”

In what’s sometimes called “risk compensation,” you would likely drive faster down the hairpin turns of a mountain road if it has sturdy guardrails than you would if nothing stood between you and those deep ravines. The sense that the environment is safer can make you comfortable taking greater risks.

By last year, the buyers of biotechnology, electric-vehicle and other “green-energy” stocks, cryptocurrencies and other hot assets had concluded their future growth would be so great it was almost impossible to overpay for them.

With so many of these stocks selling at hundreds of times their expected earnings, or not yet having any profits, the prospect of an end to the Federal Reserve’s easy-money policy hit hard this month.

Yet this was far from the first time stocks have taken a beating in recent years. The S&P 500 has closed down at least 1% for the day 448 times since the beginning of 2008, according to Dow Jones Market Data. In 2020, stocks incurred daily losses of at least 1% 45 times; on five of those occasions, stocks dropped 5% or more.

Chances are, you barely remember those declines. Investors are exceptionally adept at retroactively revising their memories. No one likes to admit fear or to feel foolish or incompetent, so we polish our own pasts; what was terrifying then becomes not so bad now.

That’s why it’s so important to understand who you are as an investor.

Falling markets set up a battle between your present self and your future self.

In 2022, your present self may be suffering anxiety and stress as you watch gains dissipate. Will you lose even more in the days and weeks to come as stocks keep lurching up and down?

“Our distant future selves feel like different people from who we are now,” says Hal Hershfield, a behavioral scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who studies how time affects people’s decisions. “It can become especially difficult to keep those distant selves in mind when there’s so many emotions in the present—in the form of temptation or fear.”

Investors should care about levels of wealth: how much money they have. Instead, they care about changes in wealth: how much they’ve just made or lost.

How happy you would be about having $1 million today depends largely on whether you had (say) $100,000 or $1.9 million last week. If you just made $900,000, having $1 million is thrilling. If you just lost $900,000, having the same $1 million will turn your stomach. That’s only natural.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

Will your future self remember the fear you felt in January 2022? Join the conversation below.

Evolution built us this way. Changes, rather than states of wealth, were what mattered to our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Even a slight shrinkage in their store of food would have spurred the clan into action. No wonder bad events and outcomes and possibilities loom larger than good ones.

Now imagine your future self is looking back at you from 2032 or 2042 or 2052. Would you remember the fear you felt in January 2022? (If you don’t believe me, see if you can describe or even recall a single investment decision you made in January 2012. I’ll wait.)

When you buy or sell stocks based on short-term market turmoil, the person you are trading with is your future self. Remember: In every trade, there has to be a winner and a loser. So who is getting the better deal?

If you have decades more investing ahead of you, then your future self is likely to be annoyed—or could even be materially impaired—by rash moves made now.

If you’re retired or about to retire, your future self may be glad you scaled back risk if stocks later decline. The same is true if you’re the kind of person who cut back on stocks in early 2020 or in 2008-09.

When you convey money from your present self to your future self, “it’s a road several hundred miles long, full of potholes and icy patches and mountain passes,” says investor and financial historian William Bernstein of Efficient Frontier Advisors in Eastford, Conn. “You can easily skid off the road unless you drive very slowly and carefully.”

He adds, “It’s better to be too conservative and end up with a few dollars less than to overestimate your tolerance for risk and end up panicking and selling at the bottom.”

Bearing your future self in mind also means you have to embrace uncertainty.

By historical standards, stocks are far from cheap at 40 times their long-term average earnings, adjusted for inflation, according to data from Yale University economist Robert Shiller. That’s among the highest in more than 140 years.

But stocks have been significantly overvalued, by the same measure, for most of the past 30 years. Had you abandoned stocks in 1992 and stayed out ever since, you would have missed out on a bonanza; stocks went on to grow at an average of roughly 11% annually over those three decades.

One reason stocks tend to have high returns over the long run is to compensate investors for the ever-present risk of losing at least half their money in the short run.

The prerequisite for being a long-term investor is knowing whether you can accept that uncertainty.

Write to Jason Zweig at [email protected]

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8