The Public Interest Legal Foundation went to Pennsylvania with a list of tens of thousands of people who were likely dead, but still on the state’s voter rolls in the weeks before the 2020 election.

The state was totally uninterested, according to Christian Adams, the organization’s founder. But once the election was over, Mr. Adams says, the state changed its tune.

It went into mediation with PILF, agreed to look into the list and even agreed to a settlement paying some of the group’s lawyers’ fees.

The kicker, though, was that Pennsylvania prosecutors even brought charges against a man who, according to PILF’s data, had registered his dead wife to vote, then requested her ballot in the 2020 election.

“All of the sudden they’re happy to settle and to clean up their rolls,” Mr. Adams told The Washington Times.

He said it’s not a fluke. The aftermath of the 2020 elections has opened new opportunities for election-integrity advocates, who say they’re seeing signs of better cooperation from at least some jurisdictions.

Last year’s contest exposed what those involved in voter administration have known for years — national elections are not an exact science, but rather an approximation of the will of voters in the weeks surrounding early November.

How close an approximation is still heatedly debated.

But it’s become clear to many that dirty voter rolls, lost or miscounted votes and mishandled ballots are more common than one might have imagined.

The difference in 2020 is that one of the candidates, then-President Trump, argued those usual flaws, combined with more preposterous speculation about machines switching votes and dumping ballots, “stole” the White House.

While the outlandish claims still have traction among some Trump supporters, the more complicated work of cleaning up the very real problems with dead people, noncitizens and other bogus voters remains.

Mr. Adams said his experience with Pennsylvania shows that in some states, the new attention from 2020 has helped.

“A virtual army has arisen of the grassroots, who are not worried about magic voting machines, and recognize the real work of election administration. These people are pressuring states to follow the law and remove dead voters,” Mr. Adams said.

But not every state is more receptive in the wake of 2020.

PILF last month sued Michigan over nearly 26,000 deceased voters whom the group says Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson won’t remove. And earlier this month PILF sued Colorado just to get a look at the state’s records on removing ineligible voters.

Those on the other side of the voter wars also are fighting back.

The League of Women Voters sued Wisconsin last week to try to force the state to “reactivate” nearly 32,000 voters who were purged from the rolls “without warning.”

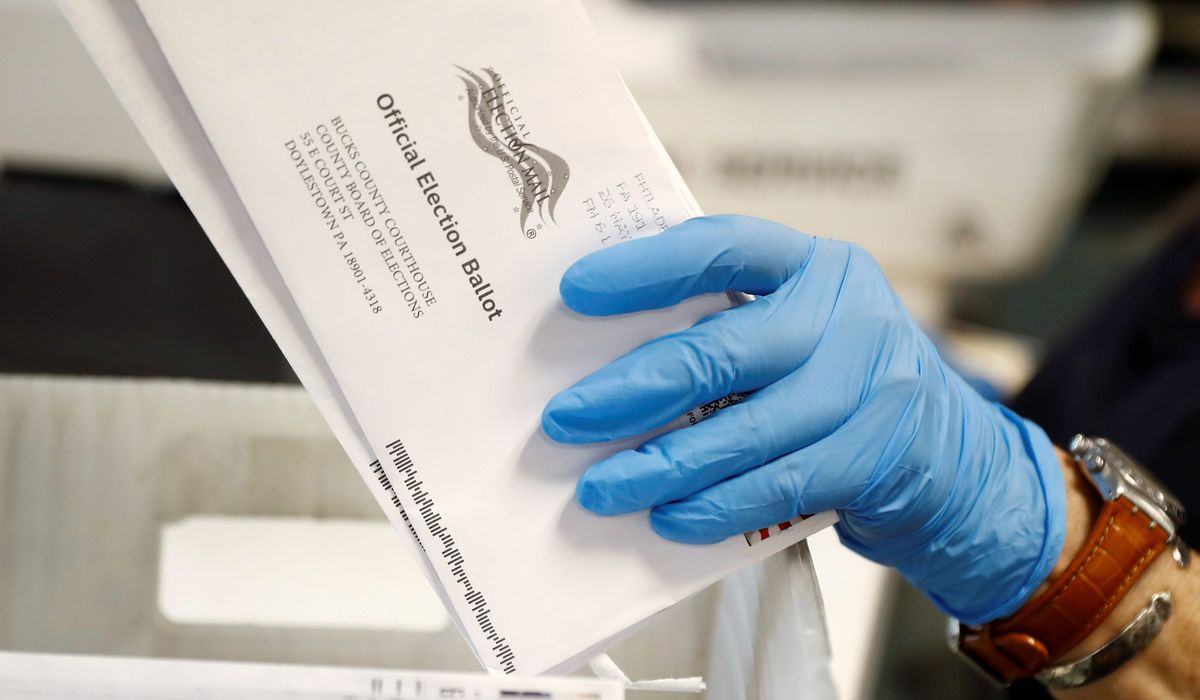

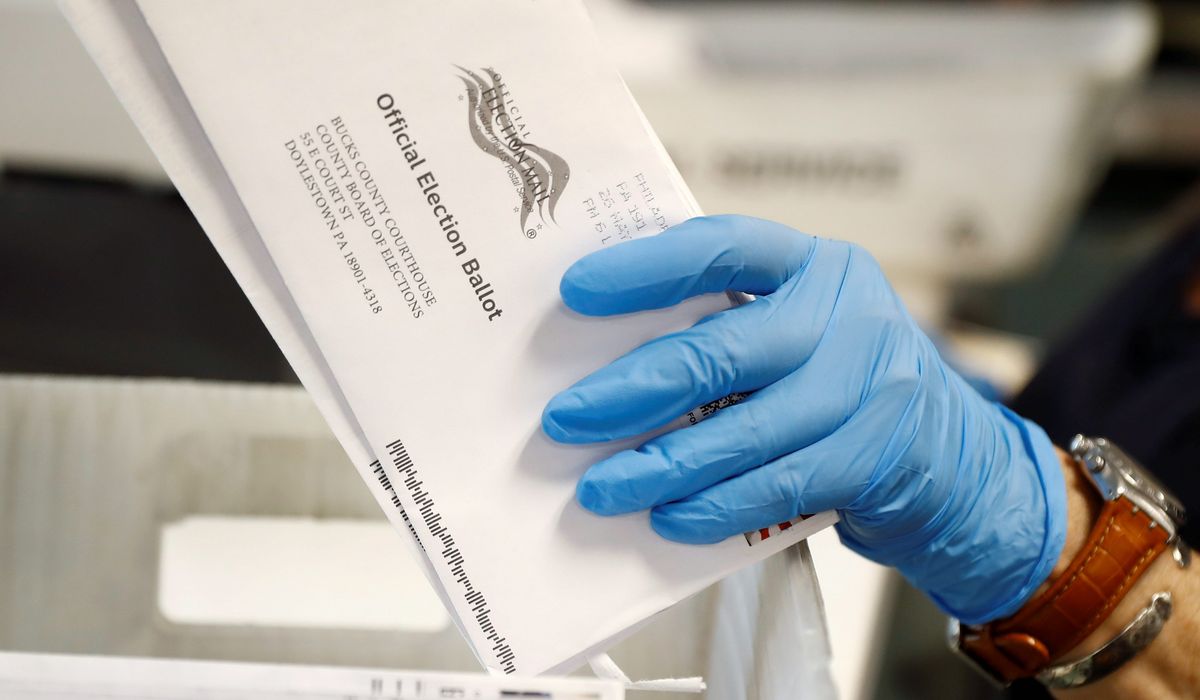

The pool of registered voters has become a battleground as states move to make it easier to vote by mail.

Voting-rights activists say striking names means legitimate but infrequent voters will have a tougher time casting ballots.

Election integrity experts say the more bad names on a list, the more chances there are for fraud.

A ballot mailed out to a deceased voter is one that can be filled out and mailed back by someone else. It’s illegal, but unless someone is out there actively looking for it, it’s tough to spot.

Mr. Adams said he’s noticed an even more worrying trend — dead voters actually registering, then voting.

That was the case for Judy C. Presto, who died in 2013. Mr. Adams has a photo of her grave.

Yet she still managed to file a registration request in August 2020, and cast a ballot in October. Prosecutors say her husband voted in her name by mail.

PILF says it found 114 people in Pennsylvania who appear to have registered to vote after their deaths were recorded.

Tom Fitton, president of Judicial Watch, another group that polices voter rolls, said the key moment for election integrity came a few years back, when the Supreme Court reaffirmed the requirement in federal law that states do have to take steps to clean up their lists.

That gives activists a hefty stick, but plenty of states are still resistant.

“Our perception is that states that are not cleaning up the rolls won’t clean up the rolls until they’re called on it,” he said.

There are some dangers to conservatives in the new focus on election integrity.

Analysts plausibly argue that Mr. Trump’s questioning of Georgia’s handling of elections helped convince thousands of GOP voters to stay home in that state’s Senate runoff elections earlier this year, costing Republicans two seats — and control of the Senate.

Still to be seen is whether Mr. Trump’s relitigation of the 2020 election will keep GOP voters at home in 2022.

But the former president has also helped a broader set of conservatives realize what’s at stake in the administration of elections.

“Conservative activists have realized they have to have a seat at the table,” Mr. Fitton said. “Typically the administration of elections has been ceded to the left, and partisans. And so conservatives are trying to get involved.”