The Senate narrowly passed a short-term debt ceiling hike on Thursday, averting a default on U.S. debts until at least December when lawmakers will face a showdown on the topic again.

In a 50-to-48 vote, legislation raising the debt ceiling by $430 billion, enough to ensure the federal government can pay its bills until at least Dec. 3, cleared the Senate. It now heads to the House where Speaker Nancy Pelosi, California Democrat, is expected to take it up next week.

“This is a temporary but necessary and important fix,” said Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer, a New York Democrat. “I appreciate that at the end of the day, we were able to raise the debt limit without a convoluted and unnecessary [party-line] process that until today the Republican leader claimed was the only way to address the debt limit.”

The vote took place shortly after lawmakers voted 61-to-38 to overcome the Senate’s filibuster threshold. Overall, 11 Republicans voted with all 50 Senate Democrats to advance the bill.

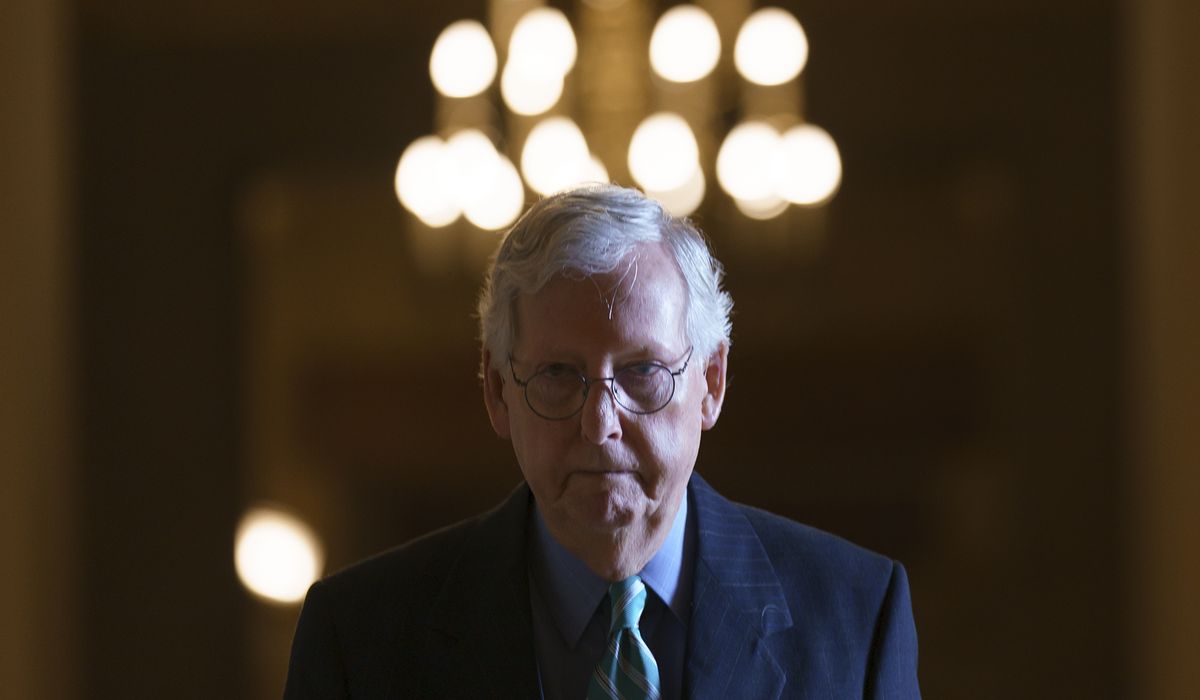

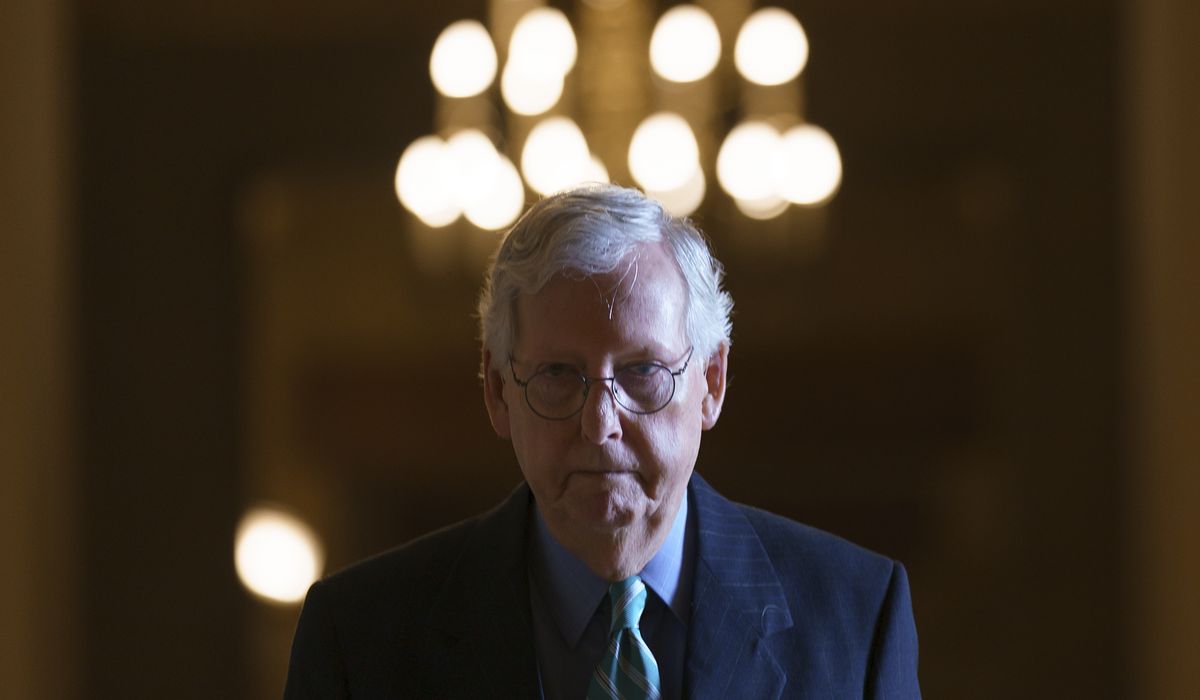

The defectors made up a wide ideological swath of the Republican conference. Three votes came from senior leadership figures — Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, Minority Whip John Thune of South Dakota, and Senate Republican Conference Chairman John Barrasso of Wyoming.

Sen. John Cornyn of Texas, a former GOP whip and likely successor to Mr. McConnell, also voted to break the filibuster. He was joined by three relatively moderate Republicans, Sens. Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, and Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia. Also joining this group was GOP Sen. Mike Rounds of South Dakota.

Retiring Republican lawmakers, including Sens. Rob Portman of Ohio, Richard Shelby of Alabama and Roy Blunt of Missouri, provided the rest of the votes.

Mr. McConnell faced internal opposition from his caucus ahead of the vote, with some even claiming GOP support for the debt limit hike amounted to a surrender.

“This is a complete capitulation,” said Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, the top Republican on the Senate Budget Committee.

Mr. McConnell offered Democrats the deal shortly before GOP lawmakers were planning to block legislation to suspend the debt ceiling until December 2022.

The GOP leader pitched the proposal as a one-time-only offer and said it would be contingent upon Democrats agreeing that further debt-ceiling increases would come via budget reconciliation.

The process, which Democrats are planning to use to ram through President Biden‘s $3.5 trillion social welfare bill, allows specific spending and tax measures to avert the Senate‘s 60-vote filibuster threshold and pass with a simple majority.

“All year the Democratic government has made unprecedented and repeated use of reconciliation to pass radical policies on party-line votes,” Mr. McConnell said. “For 2 1/2 months, the Democratic leaders did nothing and then complained that they were actually short on time. The majority didn’t have a plan to prevent default, so we stepped forward.”

Democrats and even Republicans say that by extending the offer, Mr. McConnell “caved,” rather than making Democrats move on their own.

“I’m upset with us because we had a strategy to make them pay a price to raise the debt ceiling,” Mr. Graham said. “And we blinked.”

Complicating matters is that Republicans have no way to ensure that Democrats raise the debt ceiling on their own in the future. Senior Democratic lawmakers have already ruled out using reconciliation for such a purpose.

“We’ve made it clear we’re not doing it through reconciliation. That’s a recipe for a long-term disaster,” said Sen. Christopher Murphy, Connecticut Democrat.

“Using reconciliation is a horrible precedent to set because it then will only be done in reconciliation … which will make it even harder to raise the debt ceiling,” he argued.

Democratic leaders are also wary of using the process because it would force them to specify a new amount for the nation’s borrowing limit. The number, which would be above the current limit of $28.8 trillion, opens vulnerable lawmakers to attack during next year’s midterm elections.

The motivation to avoid a potentially perilous vote was seen as one of the reasons why Senate Democrats even floated exempting action on the debt ceiling from the 60-vote filibuster hurdle.

Under the proposal, any increase or suspension of the debt ceiling would only need a simple majority of 51 votes to move forward.

For such a carve-out to be enacted, all 50 Democrats in the evenly split Senate would have needed to be on board. However, Sen. Joe Manchin III, West Virginia Democrat, signaled earlier this week he was not in favor of any changes to the filibuster.

Nevertheless, sources close to GOP leadership say that that threat was partially the reason why Mr. McConnell opted to offer Democrats a deal.

The argument appears to be backed up the fact that the Republican leader ran his offer by Mr. Manchin and other Democratic moderates before making it public.

Members of Mr. McConnell‘s caucus say the decision was wrong.

“The argument made yesterday was, ‘well, this may be more pressure than two Democratic senators can stand regarding changing the filibuster rules,’” Mr. Graham said. “That to me is not a very good reason.”

He added that if Republicans were seen caving to threats of diminishing the filibuster, it would potentially set a dangerous precedent.

“I don’t understand why here at the very end we did this … because what you’re gonna do is you’re going to embolden his folks,” Mr. Graham said. “I’m not going to live under the threat of the filibuster being changed every time we have a fight.”

Sen. Ted Cruz, Texas Republican said Mr. McConnell made a mistake.

“I believe it was a mistake to offer this deal,” he told reporters. “I don’t think it’s a good deal. And two days ago Republicans were unified. We were all on the same page. We were all standing together and making clear that Democrats had complete authority to raise the debt ceiling, and to take responsibility for the trillions of debt that they are irresponsibly adding to this country. We were winning that fight and Schumer was on the verge of surrender. And unfortunately, the deal that was put on the table was a lifeline for Schumer.”

Mr. McConnell‘s allies, including with the GOP leadership, say his deal with Senate Democrats does not amount to capitulation.

“Democrats had two things they wanted: One of them is they wanted unlimited borrowing capacity through the 2022 election and they didn’t want to put a number on it,” said Mr. Barrasso. “They don’t get either right now.”

Sen. Kevin Cramer, North Dakota Republican, said Mr. McConnell crafted an “elegant solution,” but he also believes that Democrats‘ threat to suspend the filibuster “influenced it a lot.”

“There are people around here in the Senate, and particularly, I think Mitch is one of them, for whom the filibuster is foundational to the integrity of the United States Senate,” Mr. Cramer told reporters. “I think we honor traditions a little too much around here. I think for some, that’s a big part of it.”

Others argue that a definitive resolution to the debt ceiling was never Mr. McConnell‘s end goal. Instead, they say, the Kentucky Republican wants to force Democrats into a cycle of passing mini debt-ceiling increases every few months.

Given that dispensing with the debt ceiling is a time-intensive political chore, such an outcome would delay Mr. Biden‘s agenda since lawmakers would continuously waste legislative days attempting to avert a fiscal cliff.

Mr. McConnell‘s intraparty critics say, though, such a strategy could wind up chipping away at confidence among Senate Republicans.

“If you’re retiring or in a tough contest next year, like a lot of our colleagues are, why would you take a politically risky vote when, and if, Democrats tie the debt ceiling to preventing a shutdown,” one GOP lawmaker said. “A lot of folks will say, ‘why would I vote against funding for my state’ if we’re going to just back down a few weeks later.”